25 avr. 2022

26 mars 2022

“Fore!”

from

Cities of the Red Night

by

William S. Burroughs

The liberal principles embodied in the French and American revolutions and later in the liberal revolutions of 1848 had already been codified and put into practice by pirate communes a hundred years earlier. Here is a quote from Under the Black Flag by Don C. Seitz:

Captain Mission was one of the forbears of the French Revolution. He was one hundred years in advance of his time, for his career was based upon an initial desire to better adjust the affairs of mankind, which ended as is quite usual in the more liberal adjustment of his own fortunes. It is related how Captain Mission, having led his ship to victory against an English man-of-war, called a meeting of the crew. Those who wished to follow him he would welcome and treat as brothers; those who did not would be safely set ashore. One and all embraced the New Freedom. Some were for hoisting the Black Flag at once but Mission demurred, saying that they were not pirates but liberty lovers, fighting for equal rights against all nations subject to the tyranny of government, and bespoke a white flag as the more fitting emblem. The ship’s money was put in a chest to be used as common property. Clothes were now distributed to all in need and the republic of the sea was in full operation.

Mission bespoke them to live in strict harmony among themselves; that a misplaced society would adjudge them still as pirates. Self-preservation, therefore, and not a cruel disposition, compelled them to declare war on all nations who should close their ports to them. “I declare such war and at the same time recommend to you a humane and generous behavior towards your prisoners, which will appear by so much more the effects of a noble soul as we are satisfied we should not meet the same treatment should our ill fortune or want of courage give us up to their mercy.…” The Nieustadt of Amsterdam was made prize, giving up two thousand pounds and gold dust and seventeen slaves. The slaves were added to the crew and clothed in the Dutchman’s spare garments; Mission made an address denouncing slavery, holding that men who sold others like beasts proved their religion to be no more than a grimace as no man had power of liberty over another.…

Mission explored the Madagascar coast and found a bay ten leagues north of Diégo-Suarez. It was resolved to establish here the shore quarters of the Republic—erect a town, build docks, and have a place they might call their own. The colony was called Libertatia and was placed under Articles drawn up by Captain Mission. The Articles state, among other things: all decisions with regard to the colony to be submitted to vote by the colonists; the abolition of slavery for any reason including debt; the abolition of the death penalty; and freedom to follow any religious beliefs or practices without sanction or molestation.

Captain Mission’s colony, which numbered about three hundred, was wiped out by a surprise attack from the natives, and Captain Mission was killed shortly afterwards in a sea battle. There were other such colonies in the West Indies and in Central and South America, but they were not able to maintain themselves since they were not sufficiently populous to withstand attack. Had they been able to do so, the history of the world could have been altered. Imagine a number of such fortified positions all through South America and the West Indies, stretching from Africa to Madagascar and Malaya and the East Indies, all offering refuge to fugitives from slavery and oppression: “Come to us and live under the Articles.”

At once we have allies in all those who are enslaved and oppressed throughout the world, from the cotton plantations of the American South to the sugar plantations of the West Indies, the whole Indian population of the American continent peonized and degraded by the Spanish into subhuman poverty and ignorance, exterminated by the Americans, infected with their vices and diseases, the natives of Africa and Asia—all these are potential allies. Fortified positions supported by and supporting guerrilla hit-and-run bands; supplied with soldiers, weapons, medicines and information by the local populations … such a combination would be unbeatable. If the whole American army couldn’t beat the Viet Cong at a time when fortified positions were rendered obsolete by artillery and air strikes, certainly the armies of Europe, operating in unfamiliar territory and susceptible to all the disabling diseases of tropical countries, could not have beaten guerrilla tactics plus fortified positions. Consider the difficulties which such an invading army would face: continual harassment from the guerrillas, a totally hostile population always ready with poison, misdirection, snakes and spiders in the general’s bed, armadillos carrying the deadly earth-eating disease rooting under the barracks and adopted as mascots by the regiment as dysentery and malaria take their toll. The sieges could not but present a series of military disasters. There is no stopping the Articulated. The white man is retroactively relieved of his burden. Whites will be welcomed as workers, settlers, teachers, and technicians, but not as colonists or masters. No man may violate the Articles.

I cite this example of retroactive Utopia since it actually could have happened in terms of the techniques and human resources available at the time. Had Captain Mission lived long enough to set an example for others to follow, mankind might have stepped free from the deadly impasse of insoluble problems in which we now find ourselves.

The chance was there. The chance was missed. The principles of the French and American revolutions became windy lies in the mouths of politicians. The liberal revolutions of 1848 created the so-called republics of Central and South America, with a dreary history of dictatorship, oppression, graft, and bureaucracy, thus closing this vast, underpopulated continent to any possibility of communes along the lines set forth by Captain Mission. In any case South America will soon be crisscrossed by highways and motels. In England, Western Europe, and America, the overpopulation made possible by the Industrial Revolution leaves scant room for communes, which are commonly subject to state and federal law and frequently harassed by the local inhabitants. There is simply no room left for “freedom from the tyranny of government” since city dwellers depend on it for food, power, water, transportation, protection, and welfare. Your right to live where you want, with companions of your choosing, under laws to which you agree, died in the eighteenth century with Captain Mission. Only a miracle or a disaster could restore it.

13 mars 2022

The children's mother put a dime in the machine and played "The Tennessee Waltz," and the grandmother said that tune always made her want to dance. She asked Bailey if he would like to dance but he only glared at her. He didn't have a naturally sunny disposition like she did and trips made him nervous. The grandmother's brown eyes were very bright. She swayed her head from side to side and pretended she was dancing in her chair.

12 mars 2022

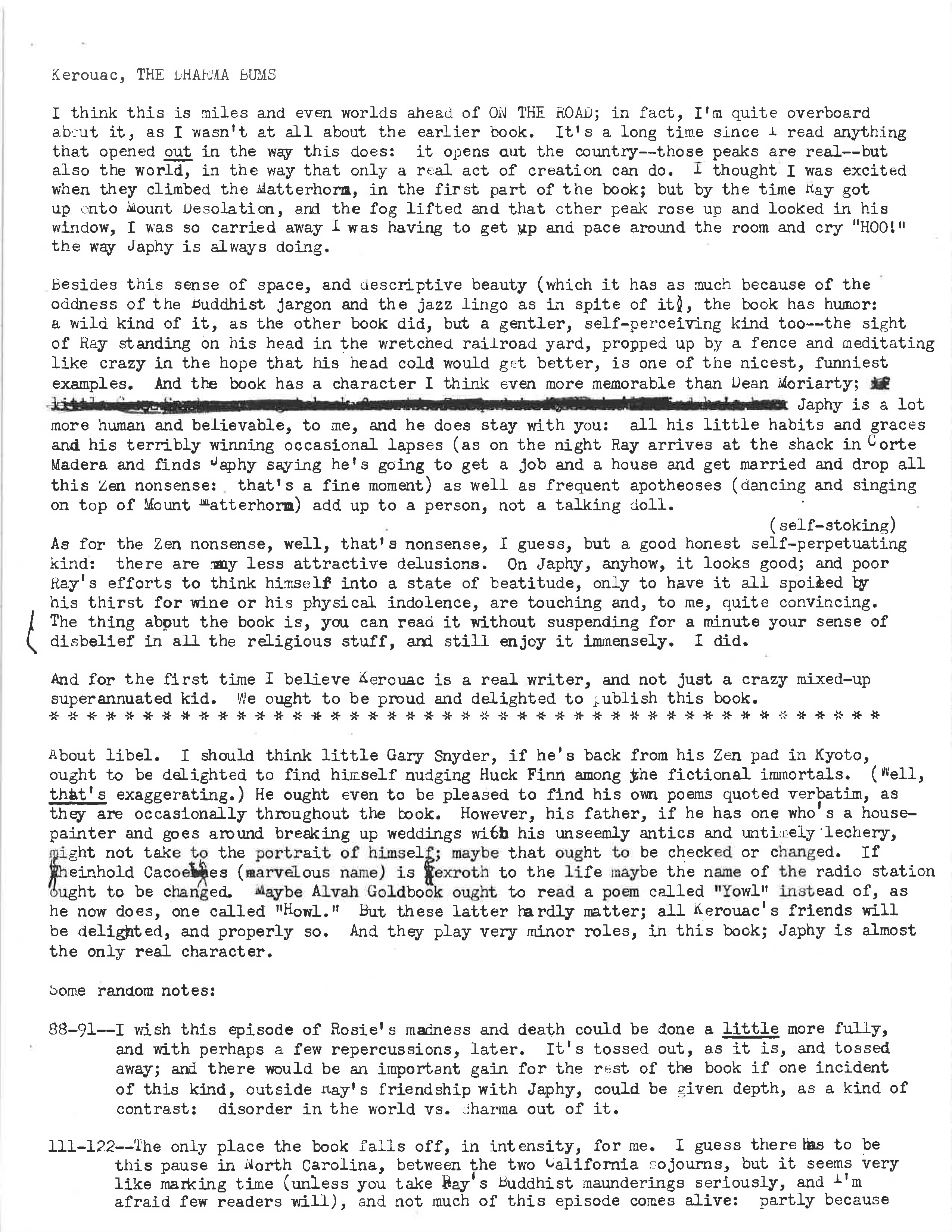

Viking & Kerouac

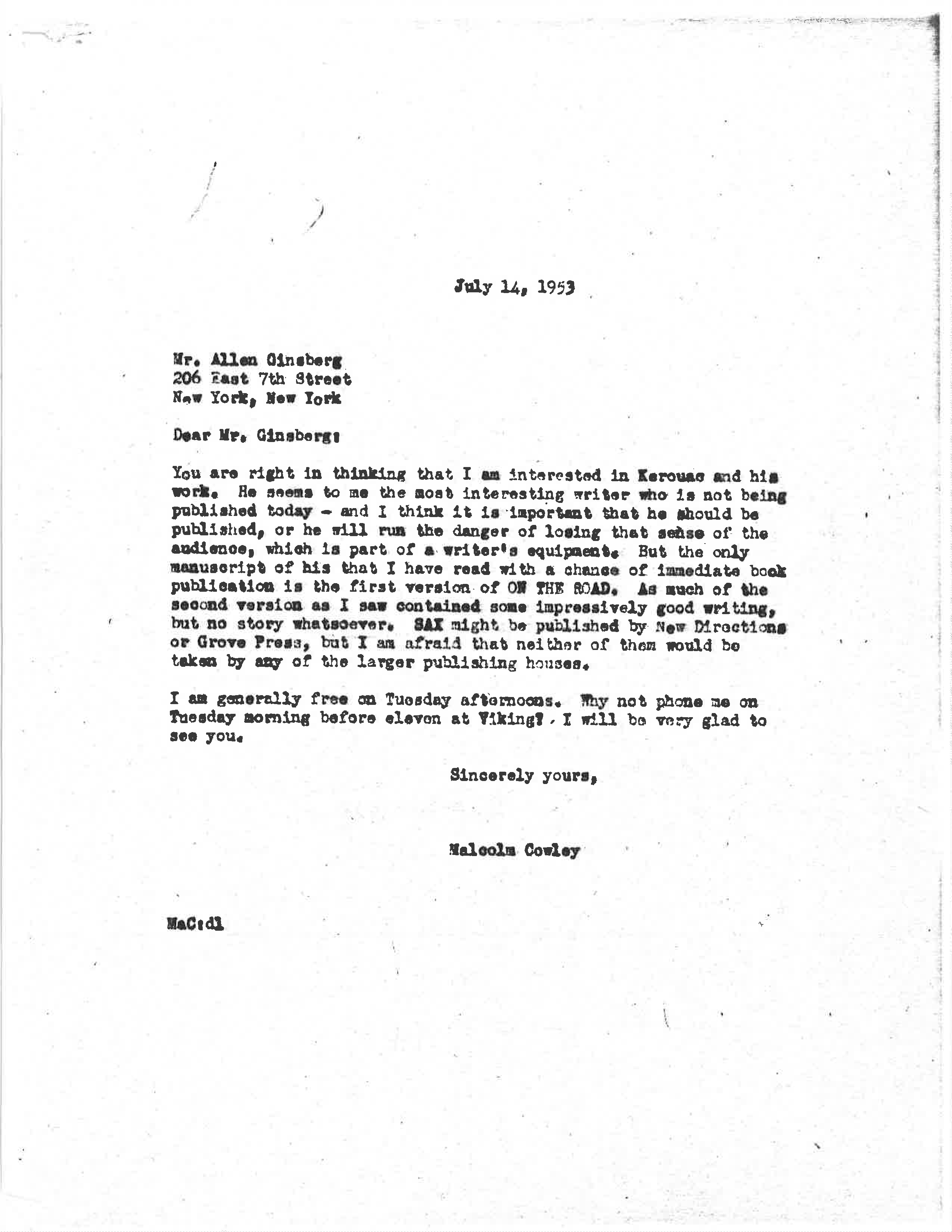

Lettre de 1953 du conseiller éditorial de longue date de Viking, Malcolm Cowley, à Allen Ginsberg indiquant l'intérêt de Viking pour Kerouac.

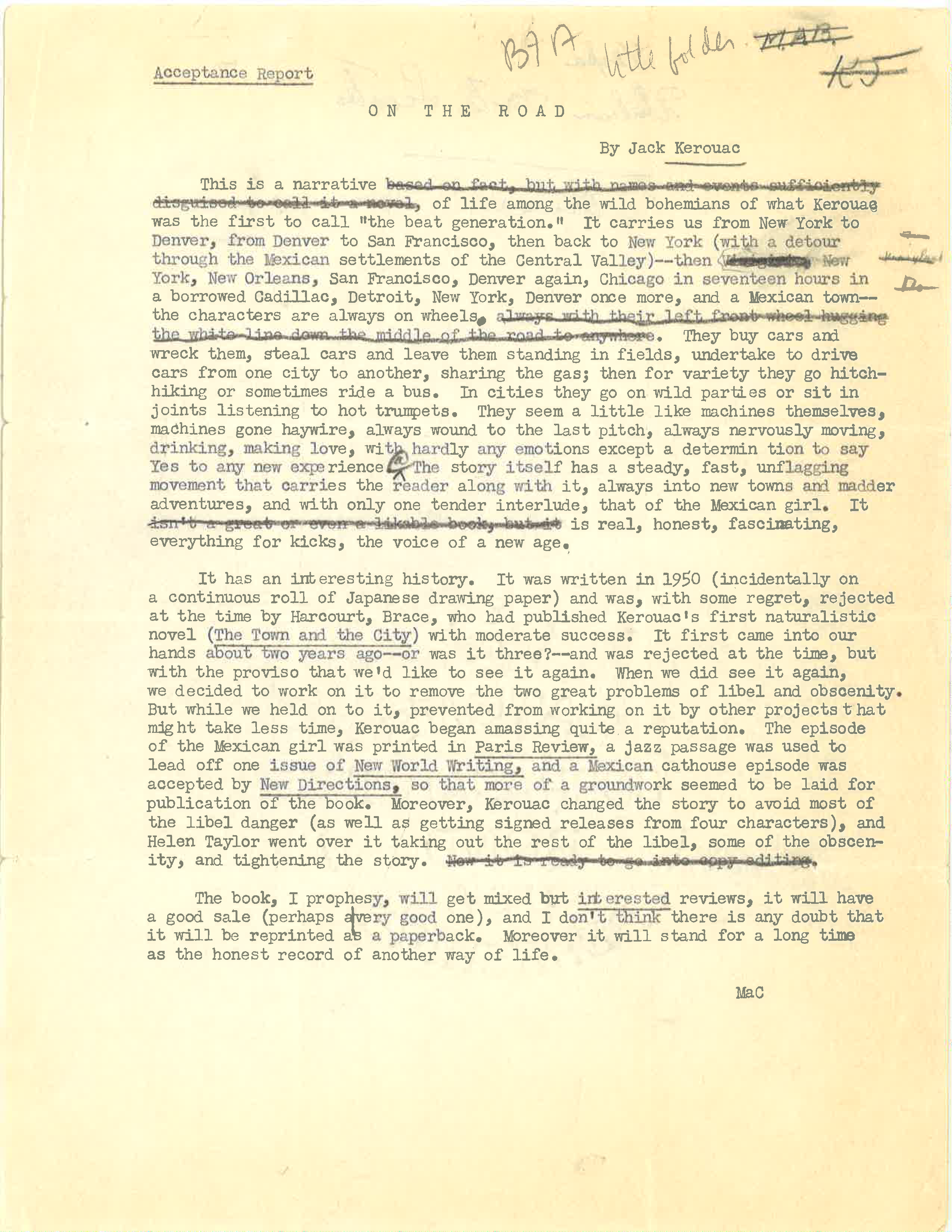

Lettre de 1953 du conseiller éditorial de longue date de Viking, Malcolm Cowley, à Allen Ginsberg indiquant l'intérêt de Viking pour Kerouac. Rapport d'acceptation non daté de Cowley sur la route.

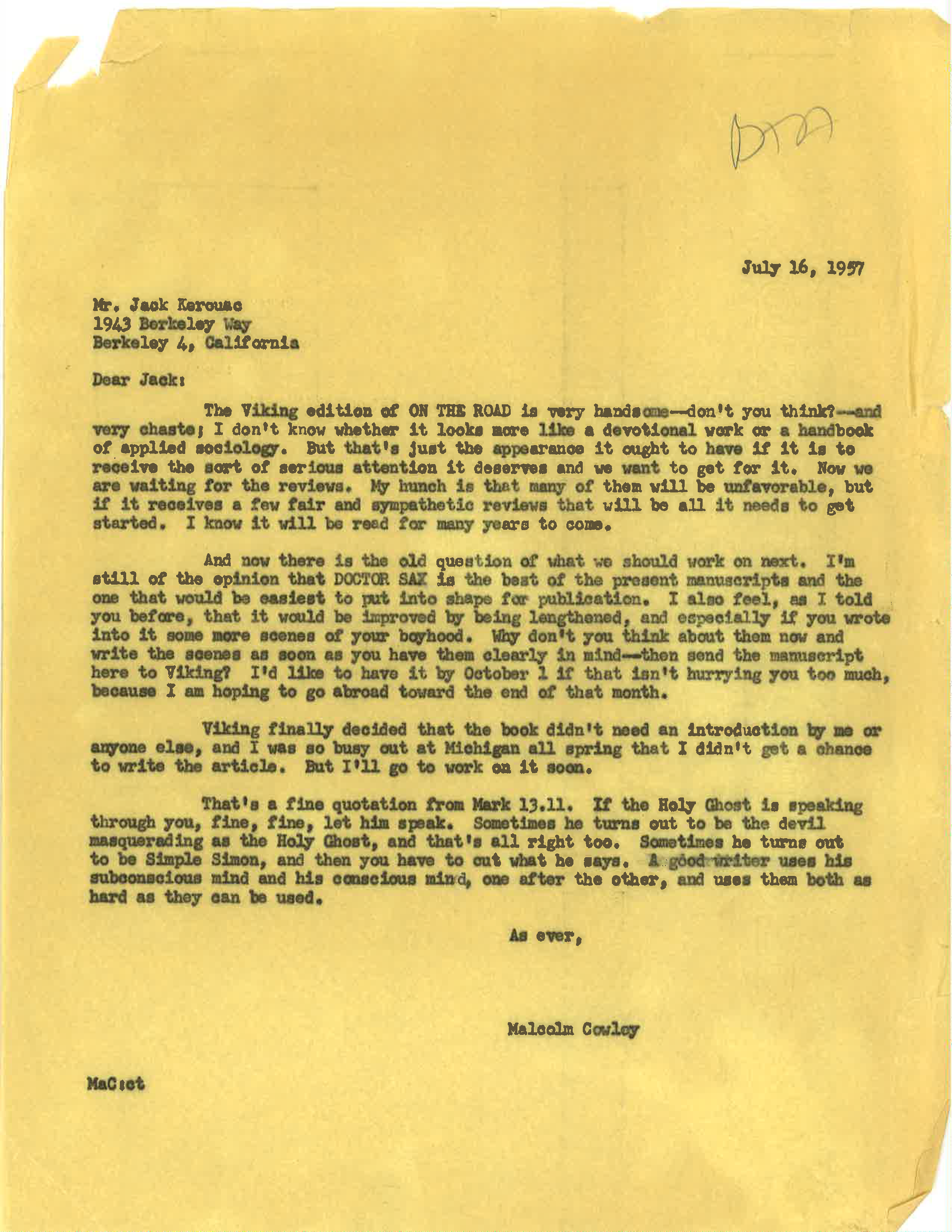

Rapport d'acceptation non daté de Cowley sur la route. Lettre de 1957 que Cowley écrivit à Kerouac à la veille de la publication de On the Road .

Lettre de 1957 que Cowley écrivit à Kerouac à la veille de la publication de On the Road . Note interne non datée de l'éditeur Viking Keith Jennison sur The Dharma Bums.

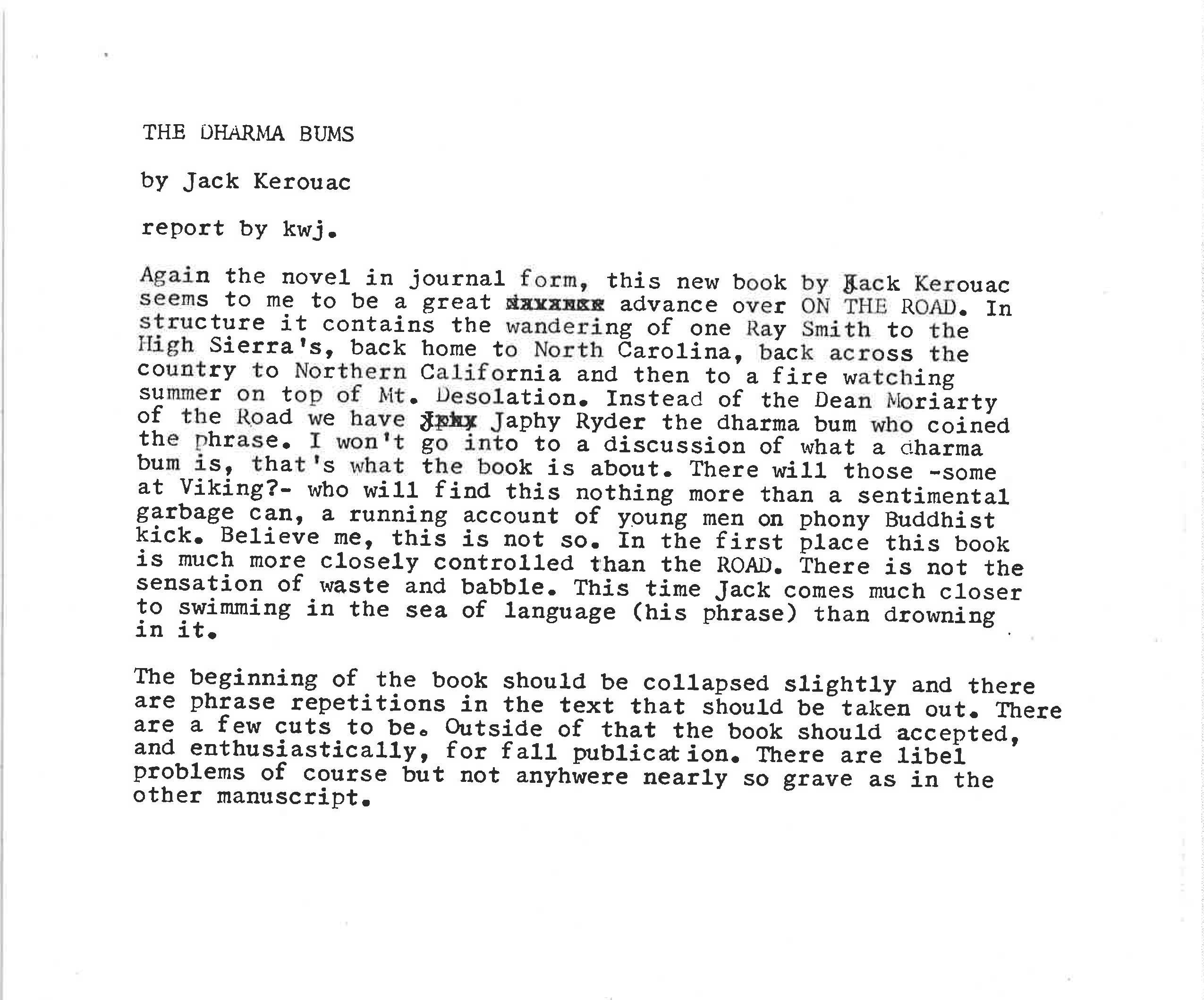

Note interne non datée de l'éditeur Viking Keith Jennison sur The Dharma Bums. Rapport interne de 1958 sur The Dharma Bums par la rédactrice viking Catharine Carver.

Rapport interne de 1958 sur The Dharma Bums par la rédactrice viking Catharine Carver.

http://www.lithub.com

4 févr. 2022

Roma – Antonioni

12 Registi_0001.avi from D Cairns on Vimeo.

19 déc. 2021

7 Delicious Recipes from

Emily Dickinson

It’s fairly common knowledge these days that everyone’s first favorite poet Emily Dickinson was also no slouch in the kitchen. In fact, as others have pointed out, in her lifetime she was almost certainly more famous for being a baker than she was for being a poet. Her creative and culinary works even seem to have influenced one another—or at least she worked on a number of poems in the kitchen, while she worked. So it’s no surprise that the Dickinson family recipes—a few of which have survived—fascinate the faithful. At least, I know that personally I decide to make one of them every year (only to become daunted or otherwise forget). So in case you’d like to impress everyone you know by arriving at your next seasonal gathering with a picnic basket full of Emily Dickinson-approved recipes (and especially if you have a boat full of eggs you need to unload), here are a few recipes to choose from. Perhaps they will even inspire some verse from your friends and neighbors.

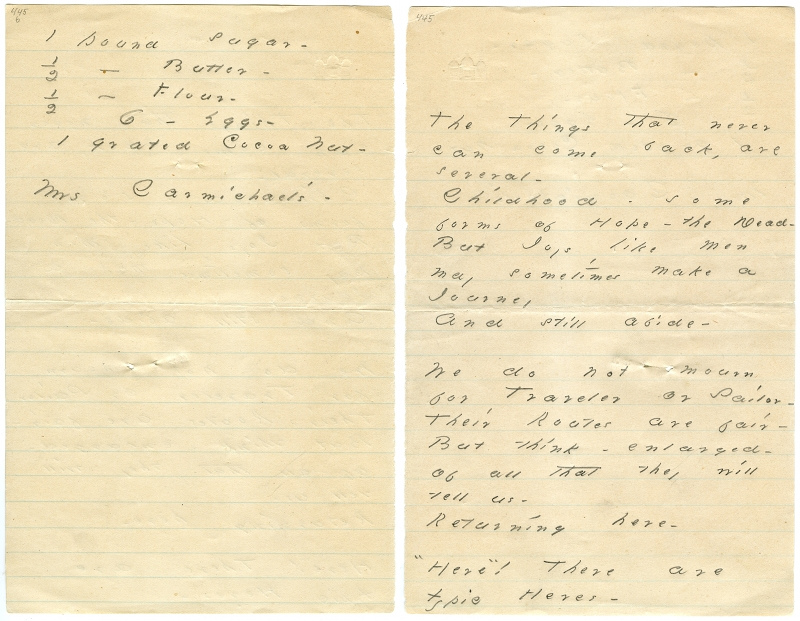

Coconut Cake:

According to the Emily Dickinson Museum website, Dickinson wrote many poems in the kitchen—often on the backs of labels, recipes and other papers, and these reveal that the kitchen “was a space of creative ferment for her, and that the writing of poetry mixed in her life with the making of delicate treats.” After all, what better way to fill the long interval between putting something good in the oven and getting to eat it? Indeed, on the back of this recipe for coconut cake, apparently passed on to her by a Mrs. Carmichael, Dickinson drafted a poem:

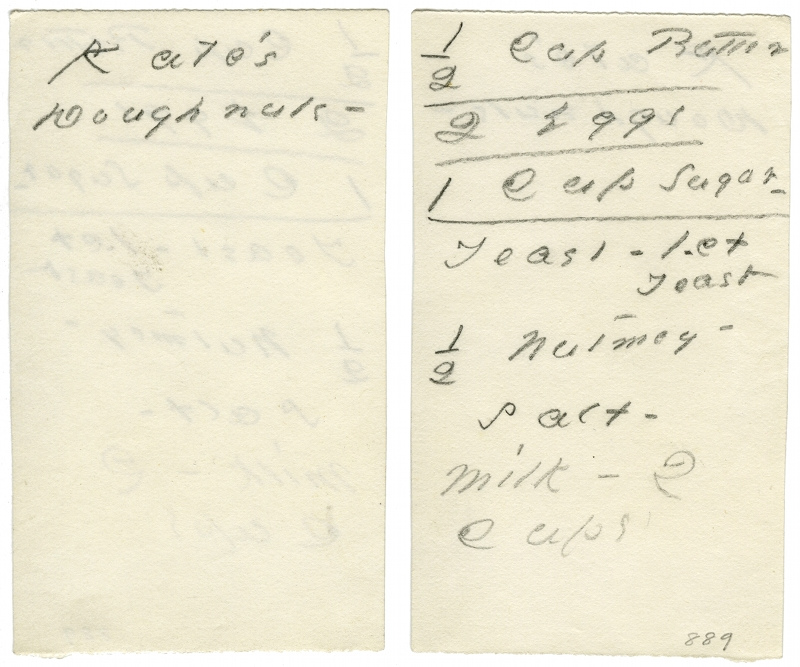

Doughnuts:

On the back of this recipe, Dickinson has written simply “Kate’s doughnuts”—the identity of Kate is a mystery. Perhaps these doughnuts were their own poems.

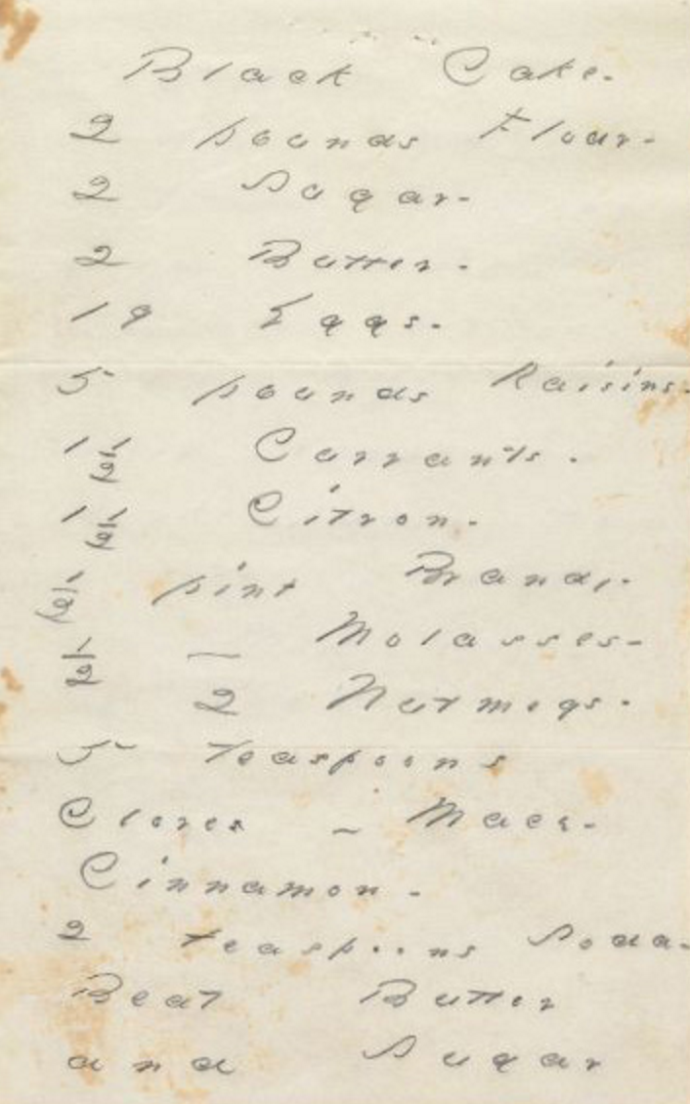

Black Cake:

The Library of America blog notes that the Dickinson family had several “lawless cake” recipes, and that Emily’s father “would eat no bread except that baked by her.” All I have to say is that 19 eggs is lawless indeed. So is the fact that, once baked, but before the brandy was poured in, this cake weighed almost 20 pounds. NB: The Washington Post published an updated version of the recipe in 1995, apparently more suited for “20th-century palates.” That one only calls for 13 eggs.

Gingerbread:

The editors of Emily Dickinson: Profile of the Poet as Cook add these instructions: “Cream the butter and mix with lightly whipped cream. Sift dry ingredients together and combine with the other ingredients. The dough is stiff and needs to be pressed into whatever pan you choose. A round or small square pan is suitable. Bake at 350 degrees for 20–25 minutes.” There is no attendant recipe for the glaze, although Dickinson did apparently glaze her gingerbread, and sometimes garnished it with an edible flower or two.

According to Emily Dickinson museum tour guide Burleigh Mutén, whenever Dickinson saw children playing in her family gardens, “she headed for the pantry, filled a basket with cookies or slices of cake—often gingerbread—carried it upstairs to a window in the rear of the house (so their mothers wouldn’t see), and attached the basket to a rope to slowly lower it to the “storm-tossed, starving pirates” or the “lost, roaming circus performers” eagerly waiting below.” When she was out of baked goods, she would send down two cups of raisins, which the children ate like candy.

Corn-Cakes:

and

Rice-Cakes:

These two recipes were originally published by Dickinson’s cousin, Helen Bullard Wyman, in a summer 1906 issue of The Boston Cooking-School Magazine. “Rice-cake was considered our very best ‘company cake’ in my childhood,” she wrote, “being carefully placed in a large tin pail, and only used when outside persons came to tea. The rule was much richer than this, however, and it was baked in sheets, very thin, and cut into squares after coming from the oven. Mace (or nutmeg) was the spice always used in it.”

Lyman’s Rye and Indian Bread

Add salt and molasses to corn meal. Pour boiling milk over it. Add cold buttermilk to the rye flour, plus baking soda. Mix entire ingredients together, adding the stewed potato. No rising time is needed. When firm, place in a round bread pan; bake at 440 degrees for 2 1/2 hours. When done, cover loaf with butter and a towel to help retain moisture.

Makes 1 loaf.

I found this one on a forum called CivilWarTalk, so my thanks to Donna from Kentucky. Lyman refers to Joseph Lyman, one of Dickinson’s cousins. Perhaps this is the very recipe with which Dickinson won second prize at the 1856 Amherst Cattle Show?

4 déc. 2021

Bibliographie d'André Dhôtel

Romans

- Campements, Paris, Gallimard, 1930 ; rééd. 1987.

- Le Village pathétique, Paris, Gallimard, 1943 ; rééd. coll. « Folio », 1975.

- Nulle part, Paris, Gallimard, 1943 ; rééd. Paris, Pierre Horay, 1956, 1977 ; Rombaldi, 1979.

- Les Rues dans l’aurore, Paris, Gallimard, 1945.

- Le Plateau de Mazagran, Paris, Éditions de Minuit, 1947 ; rééd. Paris, Guilde du livre, 1960 ; Paris, Marabout, 1977.

- David, Paris, Éditions de Minuit, 1948 ; rééd. Paris, Marabout, 1979 [roman écrit dans las années 1930].

- Ce lieu déshérité, Paris, Gallimard, 1949 ; rééd. 1997.

- Les Chemins du long voyage, Paris, Gallimard, 1949 ; rééd. coll. « Folio », 1984.

- L’Homme de la scierie, Paris, Gallimard, 1950.

- Bernard le paresseux, Paris, Gallimard, 1952 ; rééd. coll. « L'Imaginaire », 1984.

- Les Premiers Temps, Paris, Gallimard 1953 ; rééd. 1987.

- Le Maître de pension, Paris, Grasset, 1954.

- Mémoires de Sébastien, Paris, Grasset, coll. « Les Cahiers verts », 1955.

- Le Pays où l’on n’arrive jamais, Paris, P. Horay, 1955 ; rééd. Paris, J’ai lu , 1960 ; Paris, Gallimard, 1975.

- Le Ciel du Faubourg, Paris, Grasset 1956 ; rééd. Paris, Grasset, coll. Les Cahiers rouges, 1984.

- Dans la vallée du chemin de fer, Paris, P. Horay, 1957.

- Le Neveu de Parencloud, Paris, Grasset, 1960.

- Ma chère âme, Paris, Gallimard, 1961 ; rééd. Paris, Phébus, coll. « Libretto », 2003.

- Les Mystères de Charlieu-sur-Bar, Paris, Gallimard, 1962 ; rééd. Rombaldi, 1979.

- La Tribu Bécaille, Paris, Gallimard, 1963 ; rééd. 1977.

- Le Mont Damion, Paris, Gallimard, 1964.

- Pays natal, Paris, Gallimard, 1966 ; rééd. Paris, Phébus, coll. « Libretto », 2003.

- Lumineux rentre chez lui, Paris, Gallimard, 1967 ; rééd. Phébus, coll. « Libretto », 2003.

- L'Azur, Paris, Gallimard, 1968 ; rééd. coll. « Folio », 2003.

- L'Enfant qui disait n'importe quoi, Paris, Gallimard, 1968 ; rééd. coll. « Folio Junior », 1978.

- Un jour viendra, Paris, Gallimard, 1970 ; rééd. Paris, Phébus, Libretto, 2003.

- La Maison du bout du monde, Paris, P. Horay, 1970.

- L’Honorable Monsieur Jacques, Paris, Gallimard, 1972.

- Le Soleil du désert, Paris, Gallimard, 1973 ; rééd. 1997.

- Le Couvent des pinsons, Paris, Gallimard, 1974

- Le Train du matin, Paris, Gallimard, 1975.

- Les Disparus, Paris, Gallimard, 1976.

- Bonne nuit Barbara, Gallimard, 1978.

- L’Île de la croix d’or, Paris, Gallimard, 1000 soleils, 1978.

- La Route inconnue, Paris, Phébus, 1980.

- Des trottoirs et des fleurs, Paris, Gallimard, 1981.

- Je ne suis pas d’ici, Paris, Gallimard, 1982.

- Histoire d’un fonctionnaire, Paris, Gallimard, 1984.

- Vaux étranges, Paris, Gallimard, 1986.

- Lorsque tu reviendras, Paris, Phébus, 1986.

Nouvelles, récits et contes

- Du Pirée à Rhodes, Le Rouge et le noir, 1928 ; rééd. Rezé, Séquences, 1996 (suivi de Printemps grec, préface de Jean Grosjean).

- Ce jour-là, Paris, Gallimard, 1947.

- La Chronique fabuleuse, Paris, Éditions de Minuit, 1955 ; rééd. Paris, Mercure de France (éd. augmentée), 1960 ; rééd. 2000.

- L'Île aux oiseaux de fer, Paris, Fasquelle, coll. « Libelles », 1956 ; rééd. Paris, Grasset, coll. « Cahiers rouges », 2002.

- Nulle part, Paris, P. Horay, 1957.

- Les Voyages fantastiques de Julien Grainebis, Paris, P. Horay, 1957 ; 2003

- Idylles, Paris, Gallimard, 1961 ; coll. « Folio », 2003.

- La Plus Belle Main du monde, Paris, Casterman, coll. « Plaisir des contes », 1962.

- Le Robinson de la rivière, Paris, Casterman, coll. « Plaisir des contes », 1962.

- Les Lumières de la forêt, Paris, Fernand Nathan, 1964.

- Un soir, Paris, Gallimard, 1977.

- La Merveilleuse Bille de verre, Paris, Robert Laffont, 1980.

- Comment Fabien regarda l’aurore, Paris, Clancier-Guénaud, Les Premiers temps, 1982.

- La Princesse et la lune rouge, Paris, Casterman, 1982.

- Le Bois enchanté et autres contes, Paris, Hachette, 1983.

- Rhétorique fabuleuse, Paris, Garnier, 1983 ; rééd. Cognac, Le Temps qu'il fait, 1990.

- La Nouvelle Chronique fabuleuse, Paris, P. Horay, 1984.

- Pierre Marceau (Mesures, no 2, ), Paris, Mont Analogue, 1993.

- Un adieu, mille adieux, Paris, La bibliothèque Gallimard , 2003.

- Beauté, Paris, Phébus, coll. « Libretto », 2004.

- Le Club des cancres, (récit paru primitivement dans le n° 1029 du du Mercure de France) ill. et postface de Jean-Claude Pirotte, Paris, La Table Ronde, 2007.

- D’un monde inconnu, ill. de Daniel Nadaud, Saint-Clément-de-Rivière, Fata Morgana, 2012.

Poèmes

- Le Petit Livre clair, Arras, Le Rouge et le noir, 1928 ; Montolieu, Deyrolle & Théodore Balmoral, 1997.

- La Chronique fabuleuse, Paris, Mercure de France, 1960 ; ce texte et ses avatars cités plus haut peuvent être lus comme des recueils de prose poétique.

- La Vie passagère, Paris, Phébus, 1978.

- Poèmes comme ça, Cognac, Le Temps qu’il fait, 2000 (préface de Jean-Claude Pirotte).

Essais

- L'œuvre logique de Rimbaud, Mézières, Éditions de la Société des écrivains ardennais, 1933.

- Rimbaud et la révolte moderne, Paris, nrf Gallimard, 1951.

- Saint Benoit-Joseph Labre, Paris, Éditions Plon, 1957.

- Le Roman de Jean-Jacques, Paris, Éditions du Sud, 1962.

- La vie de Rimbaud, Paris, Éditions du Sud, 1965.

- Nord-Flandre Artois-Picardie, texte par André Dhôtel, photographies par Jacques Fronval, Christian de Rudder, Alain Perceval, Jacques Verroust, série Tourisme en France nr 17, Paris, Éditions SUN, 1971.

- Jean Follain, série Poètes d'aujourd'hui nr 49, Paris, Éditions Pierre Seghers, 1972.

- La littérature et le hasard, recueil de textes établi et présenté par Philippe Blondeau, Saint-Clément-de-Rivière, Fata Morgana, 2015.