LES GRANDS MUSÉES DU

MONDE ILLUSTRÉS EN COULEURS

MONDE ILLUSTRÉS EN COULEURS

LA “NATIONAL

GALLERY”

Publié sous la direction de M. ARMAND DAYOT, Inspecteur général des Beaux-Arts

OUVRAGE ILLUSTRÉ DE 90 PLANCHES HORS TEXTE EN COULEURS

PIERRE LAFITTE & Cie

ÉDITEURS :: 90, CHAMPS-ÉLYSÉES :: PARIS

1912

ÉDITEURS :: 90, CHAMPS-ÉLYSÉES :: PARIS

1912

TOME PREMIER

COPYRIGHT 1912

BY PIERRE LAFITTE & Cie

BY PIERRE LAFITTE & Cie

AVERTISSEMENT

LA “NATIONAL GALLERY” n’est peut-être pas l’un des plus

importants musées d’Europe, mais elle est à coup sûr l’un

des plus intéressants. D’autres sont plus riches en tableaux

mondialement célèbres: Amsterdam s’enorgueillit de ses

Rembrandt, le Prado de ses Velazquez, l’Académie de Venise

de ses Titien; aucun, le Louvre excepté, ne présente une telle

variété, une telle harmonieuse répartition dans les œuvres de

toutes les époques et de toutes les écoles. Si leur nombre n’est

pas considérable, la sélection apparaît irréprochable et chaque

maître y est représenté par des toiles de première valeur.

L’Angleterre, comme la France, doit ces trésors au goût artistique

de ses rois qui mettaient leur gloire à enrichir leurs palais de

belles peintures. Louis XIV et Charles Ier furent d’incomparables

amateurs d’art, et si la “National Gallery” possède aujourd’hui

cette merveilleuse collection de chefs-d’œuvre, c’est en partie

à ce magnifique et malheureux Stuart qu’elle le doit.

Cette richesse de la “National Gallery” s’est encore accrue

par des dons particuliers très importants, et aujourd’hui c’est

véritablement l’histoire de l’art tout entière, complète et admirablement

classée que le visiteur retrouve en parcourant les

vingt-cinq salles de ce magnifique musée.

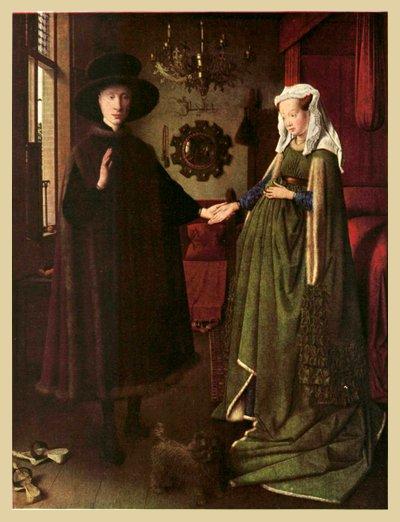

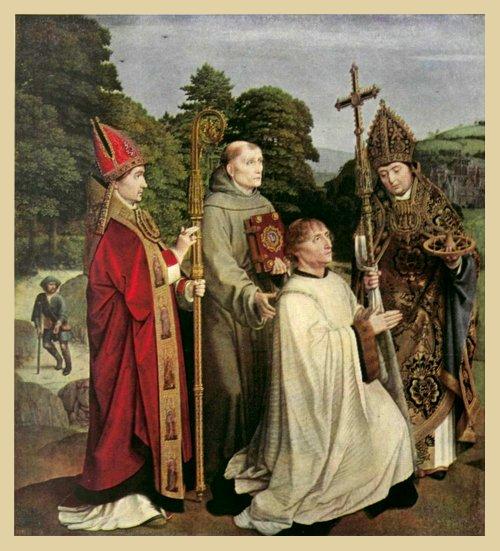

JEAN VAN EYCK

ARNOLFINI ET SA FEMME

SALLE IV.—PRIMITIFS FLAMANDS

5

Arnolfini et sa femme

LE tableau représente le couple d’Arnolfini et de sa femme dans

leur chambre nuptiale. Tout y est net, propre, rangé, comme il

sied à un intérieur de la Flandre méticuleuse. Le jeune ménage

a des habitudes d’ordre: sous les courtines à plis droits, le lit étale sa

courtepointe bien tirée. Au plafond est accroché un lustre dont les

cuivres étincelants trahissent les soins d’une diligente ménagère. Au

fond, contre le mur, s’aperçoit un miroir cylindrique de cuivre où se

reflètent la pièce et les personnages. Ceux-ci ne sont pas moins

soignés: ils sont vêtus de bonnes et solides étoffes qui dénotent

l’aisance. Les costumes, à vrai dire, sont ridicules, celui de l’homme

surtout: ils sont de cette époque dont Viollet-le-Duc disait «qu’ils

semblent issus de l’étude du laid et du difforme». Engoncée dans son

vaste chapeau, la maigre silhouette d’Arnolfini nous apparaît plus

falote encore sous l’ampleur inusitée de son manteau. La femme n’est

pas plus séduisante avec son vêtement étriqué par le haut et

démesurément large à partir de la ceinture. Sa coiffure ne l’avantage

pas non plus: cette sorte de coiffe aplatie sur le front et dissimulant

les cheveux enlève toute grâce au visage. Mais quelle expression dans

l’attitude et quelle vérité dans les physionomies! La jeune femme

pose affectueusement sa main dans celle de son époux. La douceur

des regards dit bien le sentiment mutuel qui anime ces deux êtres:

tendresse sérieuse et protectrice chez l’homme, affection reconnaissante

chez la femme à qui sont promises les joies prochaines de la

6

maternité. A leurs pieds se tient un caniche, symbolisant la fidélité

conjugale.

Arnolfini, comme son nom l’indique, était Italien. Envoyé à Bruges

comme représentant d’une grande maison de commerce de Florence,

il occupait dans la ville flamande une situation considérable, assez

analogue à celle de nos consuls modernes. En sa qualité de Florentin,

il aimait les arts et, sans que la preuve irréfutable en soit faite, on a

tout lieu de croire qu’il commanda pour son pays différents tableaux

à Jean Van Eyck. Durant son séjour en Flandre, il épousa Jeanne de

Chenany, jeune fille d’excellente famille et fort bien dotée, celle-là

même que représente le tableau.Pendant assez longtemps, on a cru reconnaître dans ce couple, le portrait de Jean Van Eyck et de sa femme, et l’on s’est basé, pour défendre cette opinion, sur l’inscription que porte la peinture: Johannes de Eyck fuit hic, et que l’on traduit ainsi: «Jean de Eyck fut celui-ci.» A cela, d’autres critiques répondent avec non moins de raison que la phrase latine signifie également «Jean de Eyck fut ici», ce qui ne prouve pas qu’il était le personnage du tableau, mais plus vraisemblablement son auteur.

En outre, si nous ne possédons aucun moyen d’identifier les traits du peintre, il nous est par contre très facile de nous convaincre par comparaison que la jeune femme représentée ici ne peut être celle de Jean Van Eyck. Celui-ci a laissé de sa femme un magistral portrait, actuellement au musée de Bruges, et on n’y constate aucun point de ressemblance avec celle-ci. Il semble donc acquis qu’il s’agit bien d’Arnolfini et de sa femme et non pas du célèbre auteur de l’Adoration mystique de l’Agneau.

Nous avons pensé que nul peintre n’était mieux indiqué que Jean Van Eyck pour figurer en tête de la série des chefs-d’œuvre de la “National Gallery”. Tout le marque pour cette place de choix: son merveilleux talent et surtout l’influence prépondérante qu’il exerça 7 non seulement sur la peinture flamande, mais encore sur la peinture universelle. N’oublions pas qu’on lui doit, sinon l’invention, du moins l’utilisation de l’huile mélangée à la peinture. Avant lui, on ne peignait qu’à la détrempe, procédé qui exigeait une très grande rapidité d’exécution et dont le moindre défaut était de sécher très lentement.

La “National Gallery” est particulièrement riche en œuvres de Jean Van Eyck, d’œuvres authentiques s’entend, car les tableaux attribués à cet artiste abondent dans les musées d’Europe. Les quelques portraits qu’elle possède sont admirables, mais le plus populaire, le plus parfait aussi, est celui d’Arnolfini et de sa femme.

Ce tableau éprouva des vicissitudes diverses au cours des siècles. On ne sait comment il sortit des mains de son premier propriétaire. Sans doute, il passa dans celles du duc de Bourgogne, Philippe le Bon, protecteur et ami de Van Eyck: en tout cas nous le trouvons, au XVIe siècle, dans la galerie de Marguerite d’Autriche, suzeraine des Flandres, qui raffolait de peinture. Par quelle étrange suite d’aventures échoua-t-il dans la boutique d’un barbier de Bruges, c’est ce qu’on ne saurait dire. Plus tard, le tableau prit la route d’Espagne dans les coffres de Marie de Hongrie; puis, sans aucune raison connue, il retourne en Belgique, dans une maison particulière où il orne la chambre d’un officier anglais, blessé à Waterloo, qui l’achète, l’emporte en Angleterre et, à sa mort, en fait don à la “National Gallery”.

Ce tableau, peint sur bois, figure aujourd’hui dans le grand musée anglais, à la salle des Primitifs flamands.

Hauteur: 0.84.—Largeur: 0.62.—Figures 0.67.

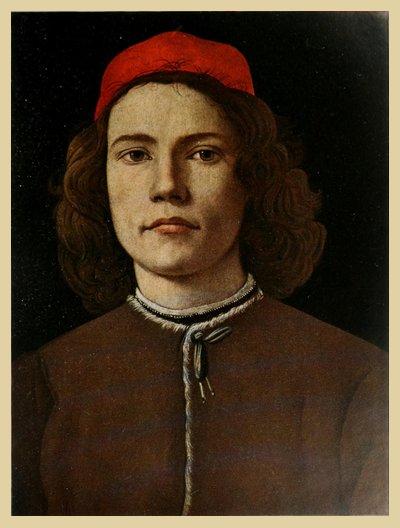

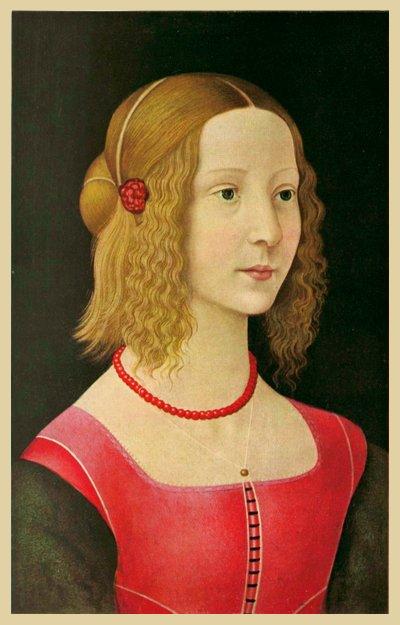

BOTTICELLI

PORTRAIT DE JEUNE HOMME

SALLE III.—ÉCOLE TOSCANE

11

Portrait de jeune homme

PARLER de Botticelli, c’est évoquer une des plus glorieuses

périodes de l’Histoire de l’art que le monde ait jamais connues,

c’est faire revivre toute une œuvre de fraîcheur, de joliesse,

de mysticité chrétienne et de charme païen, c’est rappeler cette

prodigieuse floraison spontanée dont Laurent de Médicis favorisa

l’épanouissement et qui porta ces rameaux illustres qui s’appellent

Léonard de Vinci, Michel-Ange, Ghirlandajo et Botticelli.

Dans cette brillante cohorte florentine, honneur de la peinture

universelle, Sandro Botticelli n’occupe pas la place la moins

honorable. S’il ne produit pas l’étrange fascination que provoque

Léonard de Vinci, ni la titanique puissance de Michel-Ange, il a plus

de fermeté que Ghirlandajo, avec moins de sécheresse dans la ligne

et plus d’onctueux dans la couleur. Dessinateur de premier ordre, il

conserve quelque chose de la suavité de son maître, Filippo Lippi, le

doux peintre des Madones et des Adorations. Son pinceau cherche

toujours sur la palette, les couleurs délicates, de même que son

crayon s’attarde plus volontiers aux créations gracieuses et tendres.

Toute sa vie, il est resté le peintre du Printemps; toutes ses

œuvres ont cette jeunesse, cette grâce adorable de nymphes blondes

s’ébattant dans les fleurs. Sa perfection et sa pureté sont devenues

classiques; son génie subtil, sa nature de mysticisme élégant, son

réalisme nuancé d’antique constituent une personnalité à part,

séduisante à étudier dans ses moindres détails.12 D’un génie très souple et très divers, Botticelli appliqua ses éminentes qualités de dessinateur et de coloriste aux sujets les plus différents; il peignit avec la même supériorité les scènes religieuses et les tableaux mythologiques. Un air de famille se reconnaît en toutes ses œuvres; ses déesses portent sur le front un cachet mystique qui les fait ressembler à des Vierges surprises de se trouver en quelque Olympe et ses Madones les plus idéales ont un je ne sais quoi de particulier sur le visage, une joliesse sous la couronne blonde des cheveux, qui dégage un subtil et délicat parfum de paganisme.

Botticelli fut essentiellement un Florentin, comme Dante lui-même, et c’est à Florence, dans sa ville natale, qu’on peut l’apprécier complètement. A part un bref séjour à Rome, où il peignit des fresques pour la Sixtine, il ne quitta guère sa patrie qu’il aimait et où l’attachaient ses relations artistiques et son dévouement aux Médicis.

Laurent le Magnifique, prince froid et dur comme tous ceux de son époque, possédait cependant une âme ouverte aux beautés de la poésie et des arts; son palais était l’asile d’un groupe brillant où voisinaient, avec les artistes, les philosophes et les savants.

Taine, dans son Voyage en Italie, en parle ainsi: «Laurent de Médicis accueille les savants, les aide de sa bourse, les fait entrer dans son amitié, correspond avec eux, fournit aux frais des éditions, patronne les jeunes artistes qui donnent des espérances, leur ouvre ses jardins, ses collections, sa maison, sa table, avec cette familiarité affectueuse et cette ouverture de cœur sincère et simple, qui mettent le protégé debout à côté du protecteur.»

Sous l’influence de ce puissant et bienveillant patronage, Sandro Botticelli s’épanouit magnifiquement. Aimé pour son caractère facile et tendre, il ne trouva dans ses rivaux de gloire, que des amis. La vie lui fut douce et il connut tout jeune les joies de la célébrité. Florence l’admirait et tout ce que la ville possédait de distingué 13 se disputait la faveur de poser devant lui. Et c’est alors que se révèle son merveilleux talent de portraitiste. N’eût-il pratiqué que ce genre, son nom serait resté gravé en traits immortels sur le livre d’or de la peinture et la Naissance de Vénus et le Printemps ne sauraient faire aucun tort à ces admirables portraits, si purs de dessin, si précieux de couleur, si vivants d’expression.

Il peignit la famille de ses protecteurs, les Médicis. On ne saurait rien voir de plus parfait que les portraits de Julien de Médicis et de sa chère Simonetta, dont la physionomie charmante lui servit plusieurs fois de modèle dans ses tableaux. Botticelli excellait surtout dans les portraits de femmes; il en traduisait, avec un art supérieur, le charme délicat et il y ajoutait cette gracilité qui le distingue. S’il aimait moins peindre les hommes, il ne déployait pas moins de virtuosité à exprimer le caractère de son modèle.

Est-il rien de plus vivant, de plus sincère, de plus brillant que ce Portrait de jeune homme que nous donnons ici? Où trouver un dessin plus ferme, un modelé plus savant, des chairs plus réalistes? Et cependant, sur cette effigie d’adolescent aux traits accusés, presque durs, on aperçoit cette chose indéfinissable, faite de douceur et de grâce qui nous rend le modèle sympathique et qui nous fait reconnaître au premier coup d’œil le tour prestigieux de Botticelli.

La “National Gallery” possède cinq œuvres authentiques de Botticelli; celle-ci est parmi les plus belles. Elle fut acquise par les Stuarts et elle figure aujourd’hui dans la salle III réservée à l’école toscane.

Hauteur: 0.37.—Largeur: 0.28.—Figure grandeur nature.

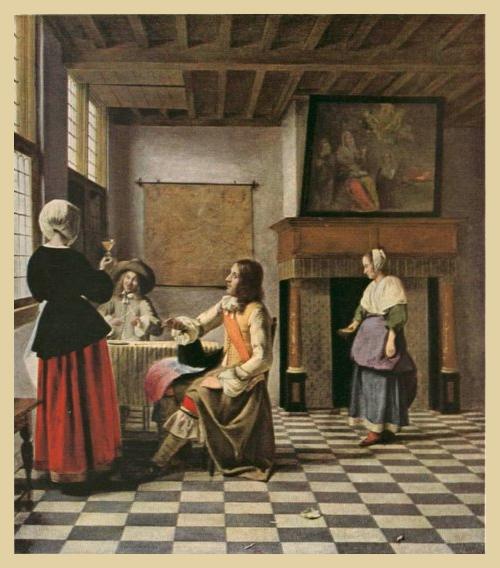

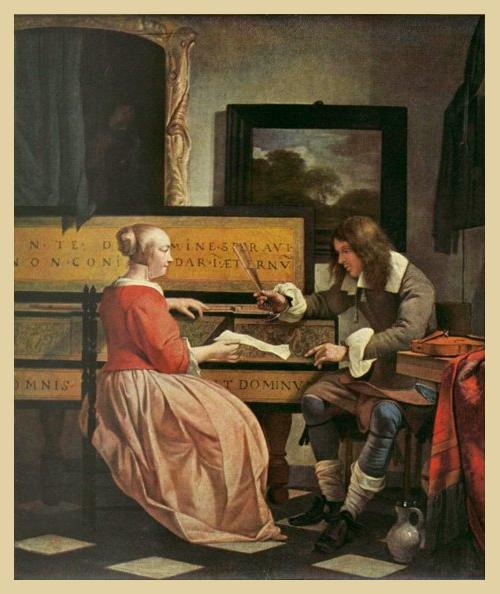

P. DE HOOCH

INTÉRIEUR HOLLANDAIS

SALLE XII.—COLLECTION PEEL

17

Intérieur Hollandais

PETER DE HOOCH est le plus charmant de ces artistes

hollandais qu’on a pris l’habitude de désigner sous le

nom de «petits maîtres.» Petits maîtres par l’insignifiance

et quelquefois la vulgarité des sujets, par l’absence de

toute pensée philosophique, de toute émotion, mais artistes supérieurs

pour la perfection de la technique, pour l’habileté de

l’exécution, pour la vérité de l’observation, pour l’admirable rendu

du détail. Parmi ces «petits maîtres» délicieux, Peter de Hooch

peut passer pour un «grand maître». Il possède les qualités

énoncées plus haut et qui sont l’apanage de tous, mais

il y ajoute ce que les autres ne possédèrent pas, le sentiment

de l’élégance et un certain laisser-aller de bonne compagnie,

grâce auquel ses personnages ne ressemblent pas tous à des

portefaix du port d’Amsterdam. Il n’a pas non plus son pareil

pour jouer avec la lumière, dont il s’est fait, en quelque sorte,

le prestidigitateur, la distribuant ou la mesurant avec un art

extraordinaire.

N’est-ce pas la lumière, en effet, qui joue le principal rôle

dans cet Intérieur hollandais que nous reproduisons ici? Par les

larges fenêtres aux vitres cernées de plomb, elle entre à flots

dans la pièce, éclairant à la fois les poutrelles du plafond et

les dalles du pavé, ne laissant aucun espace obscur. On conçoit

la difficulté, dans de pareilles conditions, de peindre un tableau

18

quelconque, sans le secours des ombres et des oppositions, et

c’est parce qu’il se plaisait à accumuler et à vaincre les difficultés

de ce genre que Peter de Hooch nous apparaît comme

un extraordinaire virtuose.Est-il possible, avec aussi peu de moyens, de donner plus de vie et d’intensité joyeuse à la scène intime qui se passe autour de la table, près de la fenêtre? Ce que font les personnages, il est assez malaisé de le dire. Nous voyons une jeune femme élevant un verre comme si elle allait boire: bien qu’on ne l’aperçoive que de dos, elle paraît chanter une chanson à en juger par l’attitude des deux hommes assis, dont l’un fait le geste de jouer du violon sur sa pipe tandis que l’autre a l’air de battre la mesure avec sa main.

L’inclination de Peter de Hooch pour l’élégance se traduit par l’introduction dans chacune de ses toiles, d’un personnage tenant du militaire et du galantin, et qui affecte les allures d’un gentilhomme. Mais on devine que l’artiste n’a pas choisi ses modèles à la cour de Versailles; il s’est assurément contenté de quelque fils de marchand jouant à l’homme de qualité, car il n’est pas possible de montrer moins de grâce sous des habits plus mal ajustés. Ce qui fait l’incomparable valeur des tableaux de Peter de Hooch, c’est l’admirable compréhension de la lumière que possédait ce peintre. A ce titre il l’emporte de beaucoup sur les peintres hollandais et flamands de son époque.

Gérard Dow n’avait pas ce maniement facile et brillant des rayons qui fait de Peter de Hooch un véritable prestidigitateur. Le seul qui pourrait lui être comparé sans trop de désavantage est Van der Meer de Delft qui semble avoir surpris lui aussi une part de ce secret.

Peter de Hooch l’emporte encore par une traduction beaucoup plus libre et beaucoup plus large de la vie hollandaise. 19 Aussi précis que Gérard Dow et Metsu, il évite de tomber comme eux dans la minutie exagérée du détail. Il y a plus d’ampleur dans sa peinture, plus d’élévation dans son style.

Mais le point par où il se rattache très étroitement à la grande famille hollandaise est dans le choix même des sujets, pris exclusivement dans le terre-à-terre de la vie quotidienne.

Il ne cherche pas en dehors de lui ni au-dessus de lui matière à tableau. Cette matière il la prend où il la trouve, à portée de sa main, et il la traite comme tous les Hollandais et Flamands d’avant et d’après lui, avec un sens du réalisme et un besoin de précision qui sont le plus grand des charmes de cette peinture minutieuse.

Il serait superflu d’y chercher une pointe quelconque d’idéalisme ou simplement une pensée de morale. Telle n’a jamais été la préoccupation de Peter de Hooch. Dans ses intérieurs, dans ses scènes d’auberge, dans tous les tableaux en un mot où il a peint la vie hollandaise, il n’a cherché ni à instruire, ni à faire penser, encore moins à moraliser.

Avant le XVIIe siècle, les Hollandais et Flamands abordaient encore fréquemment la peinture religieuse et, bien qu’ils n’y fussent pas d’une très grande inspiration, du moins y manifestaient-ils l’effort d’une pensée pieuse. Mais l’époque des dons de tableaux aux églises étant passée, les peintres de ces pays se confinèrent dans cette peinture de chevalet qui nous a valu de si nombreux chefs-d’œuvre.

L’Intérieur hollandais fut acquis assez récemment par la “National Gallery”. C’est un bijou de première valeur, qui figure dans la salle consacrée aux œuvres de la collection Peel.

Hauteur: 0.74.—Largeur: 0.64.—Figures: 0.40.

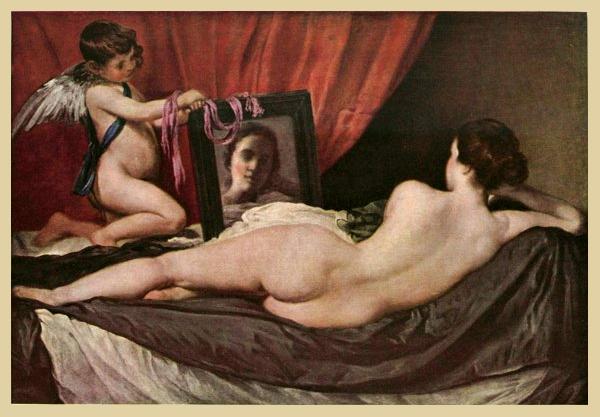

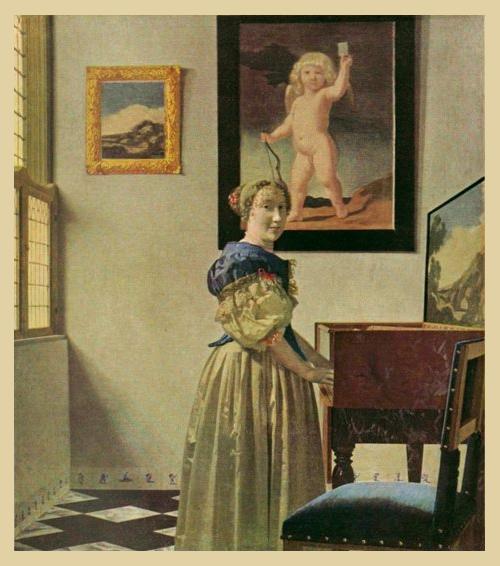

VELAZQUEZ

VÉNUS ET CUPIDON

SALLE XIV.—ÉCOLE ESPAGNOLE

23

Vénus et Cupidon

SUR un lit de repos, Vénus la blonde déesse est étendue. Elle est

vue de dos, dans une pose abandonnée qui détend tous les

muscles de son corps admirable. Son bras droit appuyé sur

l’oreiller soutient la nuque aux reflets d’or; la jambe gauche est allongée

tandis que de la jambe droite repliée, on n’aperçoit que le pied.

Sur le fond de draperie rouge qui ferme le lit, se détache la gracieuse

silhouette de Cupidon; une écharpe de soie bleue traverse en

baudrier sa poitrine et porte le carquois chargé de flèches:

ses ailes blanches s’agitent joyeusement pendant qu’il présente à

Vénus, d’un air mutin, un miroir où se reflète l’image de la déesse

des amours.

Cette page magistrale est un rare chef-d’œuvre, d’autant plus

précieux que Velazquez eut rarement le loisir de traiter des sujets

mythologiques et surtout de les exprimer sous cette forme, avec cet

emploi du nu qui fait penser aux Vénitiens de la grande époque.

S’évader des scènes religieuses était déjà une nouveauté, presque une

impiété, à une époque et dans un pays où le peintre ne devait être

que le glorificateur de la Foi et le fidèle serviteur de l’Église; mais

oser montrer une nudité et prêter tant de charmes lascifs à une

divinité païenne devait forcément choquer l’Espagne de Philippe IV,

régentée par l’Inquisition. Il fallut beaucoup de courage à Velazquez

pour risquer cette audace et sans doute se fia-t-il à l’amitié dont

l’honorait son mélancolique souverain. Il est bon de dire aussi que

24

l’artiste ajoutait à son talent de peintre le mérite d’une naissance

distinguée et l’éclat de fonctions administratives à la cour qui lui

permettaient certaines privautés. On ne l’inquiéta donc pas, mais le

parti religieux, tout-puissant à Madrid, tenait Velazquez en suspicion

et ne se privait pas d’intriguer contre lui. Sans que nul document le

démontre, on peut être assuré que le superbe tableau de Vénus et

Cupidon recueillit fort peu de suffrages et qu’il dut être considéré

comme la manifestation d’une âme corrompue.Aujourd’hui, où de telles disputes sont impossibles, nous voyons cette œuvre sous son vrai jour, avec sa vraie signification et nous admirons sans réserve cette géniale fantaisie du peintre officiel de la cour d’Espagne. Quelle admirable créature, en effet, que cette femme dans la splendeur vigoureuse de sa jeunesse et de sa beauté! Quel galbe dans ce dos et quelle finesse nerveuse et élégante dans le modelé de la jambe! Et surtout quelle vie ardente sous cet épiderme aux tons de velours où il semble que l’on voit courir le sang et palpiter les artères! Tout est charme et grâce dans ce beau corps; il faudrait du parti pris pour y apercevoir de la lasciveté; c’est uniquement le poème de la jeunesse triomphante.

Et quel art dans la composition! Comme tout est harmonieusement combiné pour donner tout son éclat à cette chair vibrante et souple! Le corps repose sur une large courtepointe de couleur grise qui fait valoir admirablement sa blancheur nacrée, de même que la charmante silhouette de Cupidon, rosée et blonde, se dore de la pourpre qui lui sert d’écran.

Comme Velazquez est Espagnol, il a choisi en Espagne le modèle de la splendide Vénus couchée. Elle a toute la souplesse des Castillanes à la taille mince et l’opulence des formes qui sont l’apanage des femmes sur l’autre versant des Pyrénées. C’est bien également un authentique visage d’Espagnole que reflète le miroir; visage aux joues pleines, où l’harmonie des lignes et la régularité des traits se 25 marient à une énergie dans l’expression qui est la caractéristique de la beauté castillane.

Ce tableau est particulièrement remarquable en ce qu’il nous montre Velazquez sous un aspect nouveau. On a l’habitude de le considérer uniquement comme un portraitiste et bien des gens se l’imaginent seulement occupé à peindre un roi morose et laid ou de petites infantes roses et frêles, embarrassées dans de rigides costumes d’apparat. Aucun génie, peut-être, ne fut aussi souple que celui de Velazquez; il aborda tous les genres avec la même maîtrise; et le même peintre qui fit les admirables portraits que l’on sait, a signé la prodigieuse toile de la Reddition de Bréda; et avec la même souplesse, il peignit des nains, des bouffons, des mendiants qui sont aussi artistiquement beaux que les plus chamarrés des gens de cour. Aussi, Velazquez restera-t-il comme l’un des plus étonnants artistes dont fasse mention l’histoire de la peinture.

Vénus et Cupidon occupe à la “National Gallery” la salle XIV réservée à l’école espagnole.

Hauteur: 1.23—Largeur: 1.75.—Figures grandeur nature.

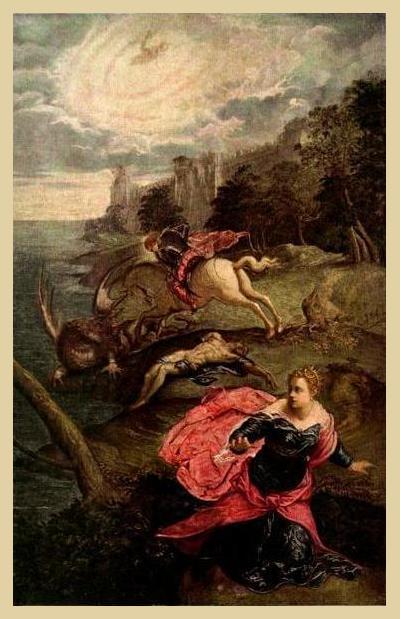

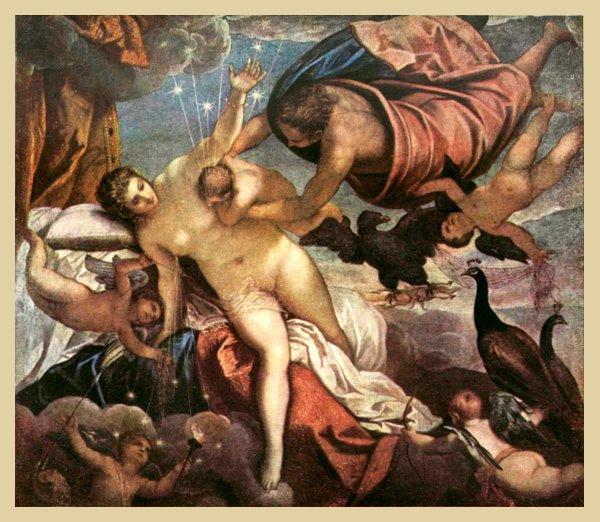

LE TINTORET

SAINT GEORGES

TERRASSANT LE DRAGON

SALLE VII.—ÉCOLES DE VENISE ET DE BRESCIA

29

Saint Georges terrassant le dragon

LA scène représente un rivage découpé pittoresquement par la

mer bleue et fermé dans le fond par une haute muraille

crénelée. De grandes masses de verdure donnent au paysage

un aspect romantique auquel ajoute un ciel tumultueux, coupé de

lueurs et de ténèbres, où roulent de lourdes nuées chargées d’orage.

Le cadre est admirablement approprié au drame qui se joue dans ce

décor. Un monstre horrible, vomi par le flot, s’est abattu sur le

rivage où se promène une princesse, venue probablement de la ville

dont on aperçoit les tours. Déjà, sa présence s’est cruellement

manifestée: une victime, étendue sur le sol, témoigne de la férocité

du monstre. Affolée, la princesse fait des efforts désespérés pour

fuir; elle s’embarrasse dans les plis de son vêtement et sans doute

deviendrait-elle à son tour la proie de la bête, si un secours

providentiel n’arrivait à point pour la sauver. Monté sur un cheval

fougueux, le bienheureux saint Georges fonce droit sur le monstre et

de sa longue lance il le transperce et le rejette à la mer.

Dans ce tableau célèbre, Tintoret a concrétisé, pour ainsi dire,

la belle légende chrétienne du Ciel protégeant la Foi contre les

attaques du Démon. La Foi se trouve représentée sous les traits de

cette princesse blonde, belle, parée de vêtements somptueux qui

symbolisent l’éclat de la vertu. Quant au Démon, l’artiste nous le

montre sous la forme la plus hideuse et la plus terrifiante, sous un

aspect capable d’inspirer à tout jamais l’horreur du péché.30 L’allégorie n’est pas seulement ingénieuse, Tintoret l’a traitée avec une vigueur et une habileté qui tiennent du prodige. Le grand Vénitien, qui se plaisait à loger dans une même toile des centaines de personnages, est parvenu à donner, dans ce tableau de dimensions restreintes, l’impression d’un drame complet réduit à trois protagonistes. Quel art dans la composition, où tout est mouvement, où tout s’accorde à augmenter l’intensité de la scène, la princesse qui s’enfuit, le cavalier qui fonce, le monstre qui se tord sous le fer meurtrier et le ciel même, où il semble que l’on voit rouler la masse épaisse des nuages.

Tintoret avait déjà traité le même sujet avec une variante. Dans le Saint Georges et la Princesse, qui se trouve au Palais ducal à Venise, la Foi, représentée par la princesse, est victorieuse du Dragon sur le cou duquel elle est assise à califourchon et qu’elle maîtrise à l’aide d’un ruban qui lui sert de bride. Derrière elle, saint Georges étend les mains comme pour bénir, tandis qu’un moine, placé à droite du tableau, contemple gravement cette scène.

Quelque remarquable que soit cette deuxième interprétation, elle est inférieure à celle que nous donnons ici, véritable chef-d’œuvre dont s’enorgueillit le grand musée anglais.

Il convient de signaler aussi le merveilleux coloris de cette toile, si harmonieux dans son éclat. Par malheur, l’action des siècles en a terni le brillant en quelques parties, mais ce qui en reste suffirait, à défaut d’autres œuvres, pour classer Tintoret parmi les plus grands coloristes du monde.

C’est une gloire peu commune que d’avoir acquis ce titre, pour un artiste qui vient à la même époque et dans la même ville que Titien et Véronèse. Élève du premier, il montra de telles qualités qu’il éveilla la jalousie du maître et dut quitter son atelier. Cela n’empêcha pas Tintoret de devenir un peintre de premier ordre et de supporter sans désavantage la redoutable comparaison avec 31 Titien. Sur les murs de son atelier, il avait écrit: «La forme de Michel-Ange, la couleur du Titien.» Tintoret réunit également ces deux qualités: il démontra victorieusement que, malgré le brio de la couleur, on pouvait être un dessinateur impeccable; et certes, il est, de tous les Vénitiens, le peintre le plus correct, le plus probe, le plus parfait.

A ces qualités fondamentales, il ajoutait une facilité d’exécution qui tenait du prodige. Cette extraordinaire facilité lui permit de peindre pour des prix très modiques un nombre considérable de tableaux, destinés aux confréries et aux églises de Venise. Tout d’abord, on ne prit pas au sérieux cet homme qui travaillait si vite et pour n’importe quel prix, si minime fût-il; ses contemporains jugeaient que le travail est la vie de l’artiste et que le gain n’est qu’une question secondaire qu’il envisagera plus tard, à l’heure du succès.

Le succès vint, et il fut glorieux. Venise ne tarda pas à l’honorer à l’égal du Titien et de Véronèse; il fut le peintre officiel des doges et des patriciens et on lui confia la décoration du Palais Ducal, sur les murs duquel il peignit sa prodigieuse fresque du Paradis.

Saint Georges terrassant le Dragon fit partie de la collection de Charles Ier d’Angleterre. Il figure aujourd’hui à la «National Gallery» dans la salle VII, réservée aux écoles de Venise et de Brescia.

Hauteur: 1.57.—Largeur: 1 m.—Figures: 0.60.

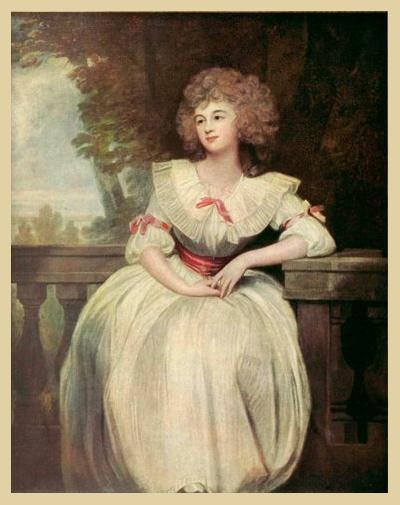

SIR JOSHUA REYNOLDS

LES GRACES COURONNANT L’HYMEN

SALLE XVIII.—VIEILLE ÉCOLE ANGLAISE

35

Les Grâces couronnant la statue de l’Hymen

ON ne peut pas dire de Reynolds qu’il fut le plus grand peintre

anglais de son temps, mais il compte parmi les plus brillants

et les plus parfaits. Gainsborough eut des qualités supérieures

aux siennes, Romney aussi nous charme par plus de grâce

aisée; mais Reynolds, né sous une heureuse étoile, reçut de la nature

des dons précieux qui, sans aller jusqu’au génie, lui permirent cependant

de produire des chefs-d’œuvre. Sa carrière d’artiste est avant tout

un miracle de la volonté. Sans avoir de dispositions exceptionnelles

pour la peinture, il devint un grand peintre à force de persévérance et

d’énergie, de même qu’il fût devenu un grand ingénieur, un savant, ou

un écrivain si les circonstances l’avaient incliné vers l’une ou l’autre de

ces professions. Reynolds fut avant tout un opiniâtre. Encore enfant,

il disait: «Je serai peintre si vous me fournissez le moyen d’être un

bon peintre.» On lui mit en main des pinceaux et son labeur acharné,

sa conscience, son étude approfondie des maîtres firent le reste. Dès

ses débuts, il détermina la voie qu’il voulait suivre; il se résolut à être

portraitiste. Et cette décision une fois prise, rien ne put le détourner

de son objet: «Mon but unique dans la vie est de peindre des

portraits et de les peindre le mieux possible.» Heureux les hommes à

qui les fées, dans leur berceau, ont déposé comme présent cette énergie

tenace que ne rebute aucun obstacle! L’avenir leur appartient et, avec

la fortune, souvent la gloire leur est promise.

L’une et l’autre échurent à Reynolds, il réalisa complètement son

36

rêve. Il fut le portraitiste le plus vanté de son époque et ne rechercha

pas d’autres lauriers. Même dans les tableaux où il aborda l’allégorie,

les personnages qu’il met en scène sont des portraits et le décor dont

il les agrémente n’y joue qu’un rôle secondaire et décoratif, uniquement

destiné à faire mieux valoir les avantages de ses modèles.Tel est le cas pour le tableau reproduit ici. Ces trois Grâces vêtues à la dernière mode londonienne du XVIIIe siècle n’ont rien de l’esthétique usitée dans ce genre de sujets; ce sont de véritables Anglaises que nul trait n’apparente aux classiques beautés que peintres et sculpteurs ont l’habitude de nous montrer. Blondes comme il sied à des filles du Nord, élancées, fines, elles ont cette fraîcheur délicate et cette grâce aristocratique dont l’Angleterre possède de si nombreux et si charmants modèles. Ces trois Grâces sont trois sœurs, filles de Sir W. Montgomery: celle de gauche, qui est agenouillée et tend des fleurs à ses compagnes, est Mrs. Beresford; celle du milieu, dont le genou ployé s’appuie sur le soubassement de la stèle, est Mrs. Gardiner, mère de Lord Blessington; enfin, nous reconnaissons la marquise Townsend dans la superbe jeune femme qui, dans ses mains levées, déploie la guirlande odorante et fleurie destinée à l’Hymen.

L’allégorie n’est donc qu’un prétexte et l’on s’en aperçoit bien. Reynolds l’a traitée à la mode du temps, conformément aux canons intronisés par la peinture française et surtout par Boucher. Le paysage est un joli décor de feuillages dorés par l’automne et l’on y voit, derrière la divinité armée de son flambeau, un magnifique rideau de pourpre tendu entre deux arbres, que l’on devine posé là comme un écran pour rehausser l’éclat de ces beautés blondes. Toutes les concessions ont été faites au goût de l’époque; Reynolds n’a pas même oublié l’aiguière ciselée que l’on aperçoit invariablement, on ne sait trop pourquoi, dans toutes les compositions allégoriques de ce temps.

Tel qu’il est, invraisemblable et apprêté, ce tableau n’en a pas moins un charme captivant. Ce qui attire surtout—et c’est bien là ce 37 qu’a voulu Reynolds—c’est la physionomie des personnages, de ces trois sœurs qui sont le sujet véritable et important de la composition.

Très habile metteur en scène, l’artiste a disposé ses modèles en des attitudes variées qui donnent à son œuvre une impression de mouvement grâce auquel il a esquivé la symétrie fâcheuse de trois portraits côte à côte.

Il convient d’admirer aussi l’heureuse distribution des couleurs, réparties en teintes douces et discrètes, d’une suprême distinction. Le coloris fut d’ailleurs la constante préoccupation de Reynolds. Dès sa jeunesse, il s’était livré à de laborieuses études des maîtres, et surtout des Vénitiens, ces maîtres entre les maîtres pour la splendeur de la palette. Il s’était évertué à surprendre leur technique, à s’assimiler leurs procédés. Il convient d’avouer cependant que, s’il les imita, ce ne fut que de façon très imparfaite; on ne pénètre pas aussi aisément dans le secret des dieux. Trop souvent ses recherches du secret des Vénitiens se firent aux dépens de ses clients dont les portraits, merveilleux à leur apparition, vieillirent plus vite que les modèles eux-mêmes; les fonds se décomposèrent et le coloris superficiel devint fantomatique. Fort heureusement, bon nombre de ses toiles ont échappé à cette disgrâce et conservent encore aujourd’hui l’éclat suprême des premiers jours. Mais, même dans les plus maltraitées par le temps, l’harmonie de la ligne demeure et classe Sir Joshua Reynolds dans la lignée des grands peintres anglais.

Les Grâces couronnant l’Hymen fut exposé à la Royal Academy en 1774. Ce tableau fut donné par le comte de Blessington à la «National Gallery», où il figure aujourd’hui dans la salle réservée à la vieille école anglaise.

Hauteur: 2.33—Largeur: 2.89.—Figures en buste grandeur naturelle.

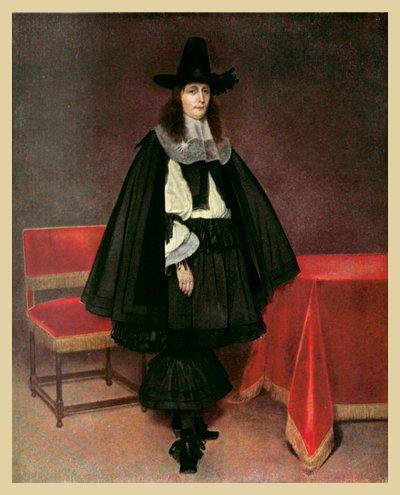

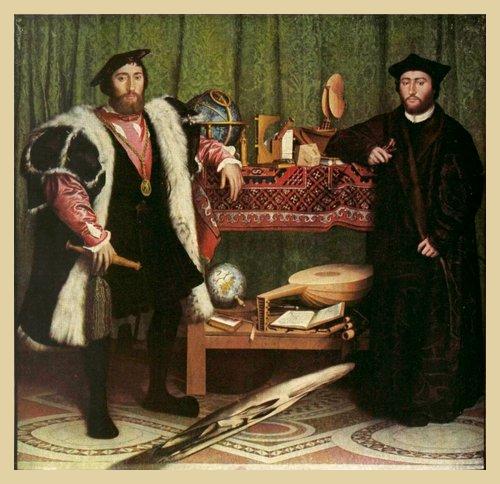

HOLBEIN

CHRISTINE DE MILAN

SALLE XV.—ÉCOLE ALLEMANDE

41

Christine de Milan

L’ORIGINE de ce magnifique portrait est curieuse et l’histoire en

est célèbre.

Holbein était venu d’Angleterre à Milan, sur les ordres de

Henri VIII, pour peindre la jeune Christine de Danemark, à peine

âgée de seize ans et déjà veuve, dont le Barbe-Bleue couronné prétendait

faire sa femme. Ambassadeur en même temps que peintre,

Holbein s’acquitta de sa mission auprès de la princesse. Mais trop

certaine du sort qui l’attendait en Angleterre, celle-ci refusa net la

couronne qu’on lui offrait:—Je n’ai qu’une tête, répondit-elle au peintre, et je tiens à la conserver sur mes épaules.

Malgré son jeune âge, cette princesse ne manquait ni d’à-propos ni de bon sens. Mais si elle éconduisit Holbein, messager matrimonial, elle consentit volontiers à poser devant un peintre dont la célébrité était universelle. Holbein se mit à l’œuvre et exécuta l’admirable portrait que nous reproduisons.

La jeune femme est debout, revêtue d’un costume sombre noué à la ceinture par un ruban. Sur ce vêtement elle porte un manteau de velours noir doublé de fourrures. Aucun ornement ne corrige la sévérité de la tenue: la duchesse porte encore le deuil de son époux, le duc de Milan, récemment décédé. Seules, la fine collerette et les poignets en dentelle éclairent le tableau. Sur la tête est posée une sorte de capuce noire qui l’enveloppe entièrement et emprisonne les 42 cheveux et les oreilles, suivant la disgracieuse mode de cette époque.

Fidèle à un procédé qui lui était habituel et que risquent seuls les grands artistes, Holbein a placé son personnage sur un fond presque aussi sombre que le sujet lui-même. Ce procédé a l’avantage de donner toute l’importance aux deux points essentiels du portrait: le visage et les mains qui, de cette manière, se détachent en vigueur. Dans ce portrait, où tout est admirable, ce visage et ces mains sont deux pures merveilles.

Sans être belle ni même régulière, la figure de la duchesse possède un charme réel qui permet de comprendre la convoitise d’Henri VIII. Il y a de l’intelligence dans les yeux, de la douceur et de la bonté dans la légère moue des lèvres. Mais ce qui se trouve exprimé avec un art incomparable, c’est la vie intérieure du modèle traduite en quelques traits légers, au moyen de frottis à peine perceptibles qui disent tout, le front plein de pensées, l’attention sérieuse et jusqu’aux sentiments de l’âme. Quant aux mains à demi fermées sur les gants, elles sont d’un galbe sans égal et on ne peut leur comparer que les mains d’Antoine Arnauld, par Philippe de Champaigne, au musée du Louvre. Fines, allongées, elles trahissent l’aristocratique naissance de la jeune femme. Elle est noble d’ailleurs dans toute sa personne. Malgré l’ampleur de son manteau, on devine une taille bien prise et des formes parfaites. Et nous pouvons certifier que telle fut Christine de Milan: car Holbein n’avait pas pour habitude de flatter ses modèles. Inexorable transcripteur de la nature, il peignait son personnage comme il le voyait, sans jamais dissimuler aucune de ses imperfections ou de ses tares. Aussi ses portraits, en dehors même de leur valeur artistique, acquièrent une importance documentaire de premier ordre.

Tel est l’attrait de cette Christine de Milan que l’œil s’obstine sur le visage et sur les mains et qu’il oublie de fouiller dans la pénombre où se dissimulent les vêtements. Et cependant l’art précis du peintre s’est exercé avec une maîtrise supérieure dans ces parties volontairement 43 obscures qu’il semble avoir voulu cacher. Quelle science et quelle perfection dans la disposition du manteau, quelle souplesse dans l’agencement des plis! Tout est beau dans cette page magistrale et l’on ne s’étonne plus qu’elle ait été disputée à coups de millions.

Holbein, dont les tableaux atteignent aujourd’hui des prix fabuleux, eut des débuts très difficiles. Il connut la gloire de son vivant, mais elle ne vint pas tout de suite. Longtemps il promena sa précaire existence dans les villes de Suisse, à Bâle, à Lucerne, peignant des portraits à vil prix pour payer sa nourriture ou solder des amendes encourues à la suite de quelque rixe dans les cabarets. Il composait des vitraux, décorait des maisons, acceptait toutes les besognes. «Tous les étrangers, dit un voyageur, s’arrêtent avec plaisir au coin d’une petite rue de Bâle, où il y a une maison, peinte au dehors, depuis le bas jusqu’en haut, de la main d’Holbein; de grands princes se pourraient faire honneur de ce travail; ce n’était néanmoins que le payement que faisait ce pauvre peintre de quelques repas qu’il y avait pris; car c’était un cabaret dont la situation aussi bien que la médiocrité marquaient assez qu’il n’était pas des plus célèbres.»

Bientôt, cependant, il se lia avec les humanistes et les réformateurs très nombreux à Bâle. Il gagna l’amitié d’Erasme et ce fut celui-ci, très influent en Angleterre, qui l’appela à la cour d’Henri VIII et contribua à sa fortune.

Le beau portrait de Christine de Milan, fut acheté par la “National Gallery” 1.800.000 francs et figure dans la salle XV, réservée à l’école allemande.

Hauteur: 1.77.—Largeur: 0.81.—Figure grandeur nature.

LÉONARD DE VINCI

LA VIERGE AUX ROCHERS

SALLE IX.—ÉCOLE LOMBARDE

47

La Vierge aux rochers

LA scène se développe dans une caverne bizarrement découpée,

en décor romantique, et formée de roches et de feuillages. Par

les ouvertures de la caverne s’aperçoivent les eaux d’un lac

bordées de rochers escarpés, et qui reflètent l’azur d’un ciel très pur.

Lumière éclatante au dehors, ombre et fraîcheur au dedans. C’est dans

cette ombre propice que le grand Léonard a placé le groupe divin.

La Vierge, moitié assise, moitié agenouillée, présente le petit Saint

Jean à l’Enfant Jésus qui le bénit de son doigt levé. Un ange à mine

charmante et fine, hermaphrodite céleste tenant de la jeune fille et du

jeune homme, mais supérieur à tous deux par son idéale beauté,

accompagne et soutient le petit Jésus comme un page de grande

maison qui veille sur un enfant de roi, avec un mélange de respect et

de protection. Une chevelure aux mille boucles, annelée et crêpelée,

encadre son fin visage d’une aristocratique distinction. Cet ange, à

coup sûr, occupe un haut grade dans la hiérarchie du ciel; ce doit être

un trône, une domination, une principauté tout au moins. L’Enfant

Jésus, ramassé sur lui-même, dans une pose pleine de savants raccourcis,

est une merveille de rondeur et de modelé. La Vierge a ce

charmant type lombard où, sous la candeur pudique, perce cet enjouement

malicieux que le Vinci excelle à rendre. Cette magistrale

peinture a noirci, surtout dans les ombres, mais n’a rien perdu de son

harmonie, et peut-être même serait-elle moins poétique si elle avait

gardé sa fraîcheur primitive et les tons naturels de la vie.48 Ce tableau, qui paraît dater de 1495, aurait été peint à Milan, par Ambrogio da Predis, sous la surveillance de Léonard lui-même et serait simplement la copie d’une autre toile semblable peinte pour la chapelle de la Conception, à l’église des Franciscains de Milan. Cette toile est celle que l’on peut admirer au Louvre, dans la Grande Galerie, sous ce même titre: La Vierge aux rochers. L’authenticité et la priorité de la Vierge du Louvre est en dehors de toute discussion: en sa présence on est, à n’en pas douter, en face de l’œuvre originale. Mais celle de la “National Gallery” dont ce musée s’enorgueillit si justement, serait-elle donc véritablement l’œuvre d’un copiste ou d’un élève? Il est impossible de le croire, lorsqu’on la contemple attentivement. Qu’Ambrogio da Predis ait collaboré à l’établissement de cette réplique, on peut l’admettre; il avait du talent et Vinci l’estimait. Mais nul autre que le Vinci n’a pu dessiner ces contours si fermes et si purs, conduire ce modelé aux dégradations savantes qui donne aux corps la rondeur de la sculpture avec tout le moelleux de l’épiderme, et rendre ses types favoris d’une façon si fière et si délicate.

Donc, si la Vierge aux rochers de la “National Gallery” n’est pas la Vierge primitive, elle n’en est pas moins une œuvre originale, merveilleuse et bien digne de porter la signature de Vinci. Tout y proclame le maître, nulle part on n’y trouve l’hésitation par où se trahirait la contribution du copiste. D’ailleurs, elle fut décrite en 1584 par Lomazzo, comme se trouvant dans la chapelle de la Conception, à l’église San Francisco de Milan, pour laquelle l’une et l’autre avaient été peintes.

Celle du Louvre, qui date de 1482, allait être livrée et mise en la place qu’elle devait occuper dans l’église, lorsqu’un différend s’éleva entre l’artiste et la Confrérie de la Conception, au sujet du paiement de la toile. Celle-ci prétendait rabattre une somme assez importante sur le prix convenu. Le conflit devint à ce point aigu, que Léonard de Vinci dut faire appel à l’intervention du duc de Milan, dans une lettre 49 récemment découverte dans les archives de cette ville. La discussion se prolongea plusieurs années, si bien que Vinci, de guerre lasse, vendit son tableau, et lorsque, enfin, les deux parties tombèrent d’accord, Léonard consentit à recommencer la toile, en collaboration avec Giovanni Ambrogio da Predis.

Quelques différences sont à noter dans cette œuvre, comparée à celle du Louvre. L’ange y est posé dans une attitude légèrement modifiée; en outre, les trois principaux personnages y sont pourvus d’une auréole d’or qui ne se trouve pas sur la peinture originale et qui semble d’ailleurs avoir été ajoutée après coup.

La Vierge aux rochers existe donc à deux exemplaires également remarquables comme exécution. Et si le Louvre possède sans conteste l’original, la “National Gallery” peut être fière de cette réplique admirable, où se manifeste la prodigieuse virtuosité du plus grand peintre de tous les temps.

La Vierge aux rochers fut apportée en Angleterre en 1777 par Gavin Hamilton; elle figure aujourd’hui à la “National Gallery”, dans la salle IX, réservée à l’école lombarde.

Hauteur: 1.84.—Largeur: 1.13.—Figure grandeur nature.

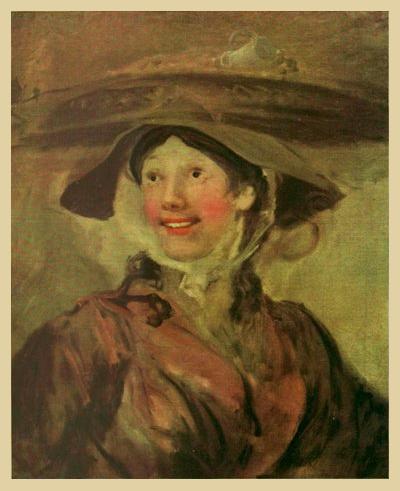

GAINSBOROUGH

Mrs. SIDDONS

SALLE XVIII—VIEILLE ÉCOLE ANGLAISE

53

Mrs. Siddons

LE modèle de cette toile légendaire était une actrice réputée en

Angleterre, vers la fin du XVIIIe siècle, pour son talent et sa

grande beauté. Elle est représentée assise de trois quarts devant

un fond de draperie rouge. Elle porte une élégante robe rayée de

bleu, garnie aux épaules et à la ceinture d’une sorte d’écharpe de

même couleur. Un grand manteau jaune bordé de fourrure drape

ce corps charmant, se pose négligemment sur les genoux et vient

s’enrouler autour du bras gauche. Avec l’une de ses mains elle maintient

un manchon de fourrures. Un large chapeau à plumes noires

encadre le délicieux visage de Mrs. Siddons, visage d’une admirable

pureté de lignes et d’une idéale délicatesse de traits, encore embelli

par l’abondante parure des cheveux poudrés qui retombent en boucles

soyeuses sur les épaules.

Dans ce magistral portrait se trouvent en quelque sorte réunies les

éminentes qualités de l’art de Gainsborough. Non pas toutes

cependant, car il y aurait injustice à oublier que le grand portraitiste

fut en même temps un remarquable peintre de paysages.Gainsborough était encore enfant lorsque s’éveilla en lui l’amour de la peinture. Avant d’avoir reçu la moindre éducation artistique, il possédait déjà cette extraordinaire facilité, cette sûreté de crayon que l’on admirera plus tard dans son œuvre.

On raconte à ce sujet une anecdote qui se place à l’époque où Gainsborough avait douze ans: l’enfant était assis dans le jardin 54 paternel à l’abri de buissons qui le dissimulaient, et copiait un vieux poirier. Tout à coup, au-dessus du mur de clôture, émergea la tête d’un paysan qui, d’un œil de convoitise, examina les fruits et, se croyant seul, en cueillit un, le plus beau. L’ardente expression du visage de l’homme frappa tellement Gainsborough qu’il la reproduisit séance tenante sur son dessin. Et si fidèle fut la traduction que le père reconnut aussitôt l’auteur du larcin et le lui reprocha.

Après un court passage dans l’atelier d’Hayman, Gainsborough se maria et quitta Sudbury, où il était né, pour se fixer à Ipswich, capitale du comté de Suffolk. Il eut la chance de s’y lier avec Philippe Thicknesse, personnage important de la province, qui le recommanda chaudement et lui procura de nombreuses commandes. Mais une querelle, d’ordre tout à fait étranger à la peinture, mit fin à leurs relations et Gainsborough abandonna Ipswich et s’installa à Bath en 1758. Il y séjourna 16 ans. Bath était alors une station à la mode, quelque chose dans le genre de notre Riviera actuelle; toute la société de Londres s’y donnait rendez-vous pendant la belle saison. Gainsborough vit les commandes affluer: bientôt les portraits en buste, qu’il tarifait au début cinq guinées, se payèrent huit, puis quatorze guinées; quant aux portraits en pied, ils ne montaient pas à moins de cent guinées.

C’est vers cette époque que Gainsborough fut saisi d’une passion subite et extraordinaire pour la musique, passion qui le posséda au point de lui faire négliger la peinture et ses intérêts. Néanmoins, son séjour à Bath marque un changement considérable et un progrès réel dans sa technique, sans doute parce qu’il put voir et étudier, dans les riches demeures des environs, les œuvres des grands maîtres du passé qu’il ne connaissait encore que très imparfaitement.

Aussi dès son arrivée à Londres, en 1774, il est en pleine possession de son talent. La notoriété l’y a déjà précédé et son atelier est assailli par tout ce que la capitale compte de distingué. Les portraits succèdent 55 aux portraits et la plupart sont des chefs-d’œuvre. Il fait déjà partie, depuis la fondation, de l’Académie instituée par Reynolds et ses envois annuels y font l’admiration des amateurs. Il cesse d’y exposer pendant quelque temps à la suite d’une brouille avec Reynolds. Les deux grands peintres se connaissent et professent l’un pour l’autre une estime réciproque, mais leurs caractères très différents s’accordent mal et ils vivent complètement éloignés l’un de l’autre. Gainsborough, qui semble avoir eu les premiers torts, a l’âme impétueuse mais bonne; et quand il sent venir sa mort, il écrit une lettre touchante à son illustre rival et lui demande de conduire ses obsèques. Il mourut le 2 août 1788, à l’âge de soixante et un ans.

Gainsborough, par l’originalité de son talent, l’élégance de sa manière, la qualité de sa couleur, demeurera comme l’une des plus hautes personnifications de l’art anglais.

Écoutons John Ruskin: «La puissance de coloris de Gainsborough a ce qu’il faut pour prendre rang à côté de celle de Rubens; c’est le plus pur coloriste, sans en excepter Reynolds lui-même, de toute l’école anglaise. On verra assez de preuves de l’admiration que j’ai vouée à Turner, mais je n’hésite pas à dire que, dans l’art purement technique de la peinture, Turner est un enfant auprès de Gainsborough. La main de Gainsborough est aussi légère que le vol d’un nuage, aussi rapide que l’éclair d’un rai de soleil. Ses formes sont grandes, simples, idéales. En un mot, c’est un peintre immortel.»

Mrs. Siddons appartint longtemps à la collection du Major Mair, qui avait épousé la petite-fille de la célèbre actrice; il figure aujourd’hui à la “National Gallery” dans la salle XVIII, consacrée à la vieille école anglaise.

Hauteur: 1.25.—Largeur: 0.99.—Figure grandeur nature.

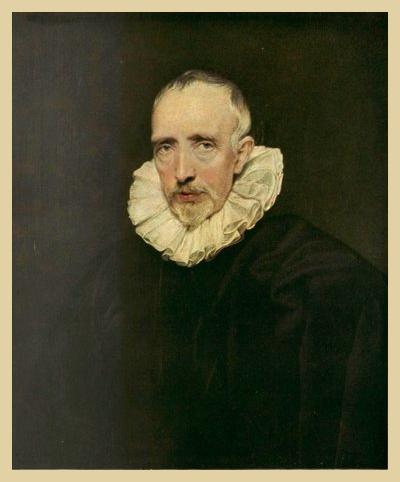

A. VAN DYCK

LES ENFANTS DE CHARLES Ier

GALERIE NATIONALE DES PORTRAITS

59

Les Enfants de Charles Ier

ANTONIO VAN DYCK—Sir Anthony Van Dyck, comme

l’appellent les Anglais—fut attiré en Angleterre par le roi

Charles Ier. Beau cavalier, causeur spirituel, esprit subtil, il

eut vite fait la conquête de la cour et de la ville. Le monarque

l’honora d’une faveur toute particulière, le nomma principal peintre

ordinaire, le créa chevalier et lui donna un logement dans le palais

royal de Blackfriars. Van Dyck ne se montra pas ingrat; il voua à son

généreux protecteur un dévouement qui ressemblait à un culte. Malgré

l’abondance de sa production, son pinceau fut surtout consacré au roi

et à sa famille. Nombreux sont les portraits de Charles Ier, on n’en

compte pas moins de trente-huit; le Louvre en possède un magnifique

exemplaire, d’une célébrité mondiale; la “National Gallery” s’enorgueillit

du portrait équestre du roi, qui ne lui est guère inférieur. Non

moins abondantes sont les effigies des divers enfants du souverain; on

en trouve à Windsor et dans les Musées du Louvre, de Dresde, de

Saint-Pétersbourg, de Turin, de Berlin. Celui que nous donnons ici

est un des plus beaux et en même temps des plus intéressants, en ce

qu’il représente toute la descendance directe du malheureux Stuart.

L’artiste a placé ses jeunes et charmants modèles sur une même

ligne, devant un fond de draperie relevée qui laisse apercevoir les

ombrages d’un parc. Au centre du tableau se tient le prince de Galles,

qui devint plus tard Charles II d’Angleterre; vêtu d’un riche costume

pourpre avec collerette de dentelle et manches à crevés, il appuie sa

60

jolie main d’enfant sur la tête d’un énorme et paisible molosse. Tout

près de lui, à gauche du tableau, est figuré son jeune frère, âgé de

quatre ans, encore en costume de fillette, qui deviendra roi à son tour

sous le nom de Jacques II; la charmante fillette de six ans qu’on

aperçoit à gauche, si mignonne sous sa parure de cheveux blonds et

qui prend déjà des airs de reine, est la princesse Marie qui sera plus

tard la mère de Guillaume III. A droite, l’enfant qui s’empresse auprès

du bébé, n’a guère plus de deux ans; c’est la princesse Élisabeth.

Quant au rose et potelé baby qui se débat dans ses langes pour

atteindre la tête du chien, c’est la princesse Anne, la dernière fille de

Charles Ier, qui mourut en bas âge.Van Dyck, uniquement préoccupé de la ressemblance de ses modèles, s’inquiétait assez peu des artifices de composition employés par certains artistes pour mettre en valeur les personnages. Il avait trop de génie pour recourir à l’habileté. Il lui importe peu de risquer la monotonie en disposant les enfants royaux sur une même ligne; ce qui compte pour lui—pour nous aussi—c’est d’exprimer exactement la physionomie de chacun d’eux. Il est à peine utile de montrer avec quel bonheur il y a réussi, avec quelle intensité il a su peindre la vie sur ces jeunes visages insouciants, aux yeux limpides, que le malheur n’a pas encore effleurés et devant qui ne se dresse pas l’effroyable avenir qui les attend. Il y a déjà, dans ces petits corps à peine formés, cette naturelle aisance, ce suprême parfum d’aristocratie qui distingua toujours la noble race des Stuarts.

Van Dyck peut être considéré comme le roi des portraitistes. D’autres, comme Rembrandt, ont marqué leurs modèles de traits plus vigoureux et plus profonds; aucun peut-être n’a possédé au même degré cette netteté de lignes, cette certitude tranquille qui ne connaît pas la défaillance. Un portrait de Van Dyck peut être comparé à tous les autres de sa main, ils sont tous également supérieurs. Absorbé et souvent distrait par la luxueuse existence qu’il menait à Londres, il lui 61 fut impossible d’exécuter lui-même toutes les commandes dont on l’assaillait. Imitant l’exemple de son maître Rubens, il s’était entouré d’une pléiade d’élèves habiles, formés par lui, qu’il chargeait d’établir la plupart de ses portraits. Mais lorsque le portrait était campé, dégrossi, il le prenait dans ses mains puissantes et, en quelques touches rapides de son pinceau prestigieux, il lui donnait sa forme définitive, il le marquait de sa griffe géniale. Le portrait devenait un authentique Van Dyck.

Il n’en usait pas avec cette liberté quand il peignait le roi Charles, la reine Henriette ou les enfants royaux. Dans ces portraits, tout est bien de sa main; elle se révèle manifestement dans la précise clarté des paysages, dans la lumineuse profondeur des ombres, dans la distinction discrète d’un coloris toujours parfait.

«Le grand Flamand», comme on appelle généralement Van Dyck, a connu cette gloire de n’avoir eu aucun détracteur au cours des siècles. Il y a unanimité d’admiration autour de son œuvre. Reynolds, peintre de portraits lui aussi, le proclamait le plus grand portraitiste qui ait jamais existé et Gainsborough mourant se réjouissait dans l’espoir de retrouver Van Dyck au ciel.

Bien qu’il ait abordé avec une maîtrise égale les sujets mythologiques et religieux, Van Dyck demeure le roi incontesté du portrait et son œuvre lui a acquis une gloire immortelle et une place de premier plan à côté des plus grands noms de la peinture.

Les Enfants de Charles Ier figurent dans la partie de la “National Gallery” consacrée spécialement aux portraits.

Hauteur: 0.58.—Largeur: 0.99.—Figures grandeur demi-nature.

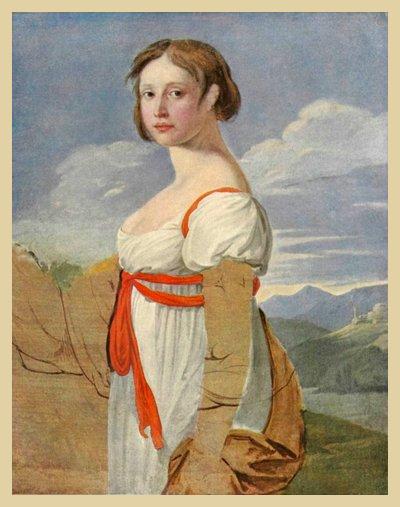

LOUIS DAVID

ÉLISA BONAPARTE

SALLE XVII.—ÉCOLE FRANÇAISE

65

Élisa Bonaparte

DES trois sœurs de Napoléon, Élisa, l’aînée, fut la plus

maltraitée du destin. Moins belle que Pauline et que Caroline,

elle eut encore la disgrâce de se voir déchirer par ses

ennemis, qui étaient nombreux: ils la disaient laide et de physionomie

revêche. Ses amis ne vantent point les charmes de son visage, mais

exaltent son esprit, son intelligence, sa perspicacité politique, sa ferme

volonté. Les uns et les autres s’accordent à constater sa très grande

ressemblance avec son frère Napoléon.

Examinons le portrait de David: tous les traits de l’illustre

capitaine s’y retrouvent. C’est le même menton volontaire et hardi, le

même regard froid, la même chevelure du «Corse aux cheveux

plats». Nous savons qu’Élisa n’était pas belle et nous pouvons croire

que David a fait effort pour adoucir la froideur du visage, mais en

dépit de tout, transparaissent la dureté des yeux et la hauteur un peu

insolente de l’attitude. Taillée en force, la tête posée sur un cou robuste

attaché lui-même à de solides épaules, elle apparaît ce qu’elle sera

toute sa vie: une femme opiniâtre, emportée dans ses exigences

comme dans ses passions. Le frais costume de jeune fille qu’elle porte

ne parvient pas à dissimuler cette rudesse native qui la rapprochait

du caractère de Napoléon. Celui-ci disait à Sainte-Hélène: «Dès son

enfance, Élisa fut fière, indépendante. Elle tenait tête à chacun de

nous. Elle avait de l’esprit, une activité prodigieuse.»Mariée à une époque où l’étoile de son frère commençait à peine 66 de briller, Élisa dut se contenter d’un obscur capitaine, Félix Bacciocchi, un Corse qui habitait Marseille, dans la même maison que la famille Bonaparte. Le ménage débuta dans l’indigence et il fallut que le jeune général de l’armée d’Italie envoyât trente mille francs pour mettre un peu d’aisance dans la vie des deux époux. Bien qu’il n’eût pas approuvé ce mariage, Napoléon, qui fut le meilleur des frères, servit de son mieux Bacciocchi, lui donna de l’avancement, des fonctions, et plus tard une couronne princière. Il fit plus encore pour sa sœur, il la débarrassa de son médiocre mari, dont elle rougissait, en l’envoyant occuper des emplois dans de lointaines ambassades.

Libre de tout lien gênant, Élisa élut domicile chez Lucien, qu’elle aimait plus que ses autres frères et qui venait de perdre sa femme. Elle y joua le rôle de maîtresse de maison et quand les brillantes fêtes que donnait Lucien reprirent leur cours, ce fut elle qui présida aux apprêts de ces nouvelles réceptions mondaines. Dans la société de ce frère préféré, où brillaient quelques hommes remarquables du monde des lettres et des arts, elle trouvait un charme qui lui semblait très doux. Son éducation à Saint-Cyr, avant la Révolution, les conversations de Lucien, ses propres lectures, tout ce passé la disposait aux jouissances intellectuelles bien plus qu’aux futilités dont se contentent les femmes. Elle se donna tout entière à ces plaisirs relevés et nobles avec la violence de sa nature. Dans ses salons se rencontraient tous les beaux esprits du temps: La Harpe, Boufflers, Esménard, Arnault, Andrieux, Joubert, Delille, Chateaubriand qui la proclamait «l’adorable protectrice des lettres et des arts», et surtout Fontanes, qui devint un peu plus que l’ami d’Élisa.

L’ambition politique ne lui vint que plus tard, lorsque Napoléon fut tout-puissant, mais elle s’empara d’elle tout entière. Elle cessa de jouer les pièces de Corneille dans le salon de Lucien et rêva de tenir des rôles plus conformes à son besoin de dominer. Les flatteries de son entourage avaient perverti son esprit et lui avaient inculqué une 67 présomptueuse assurance qui faussait son ancienne bienveillance, et les soirées de Neuilly n’avaient plus aucun attrait pour elle.

C’est avec ces sentiments absolus et ce caractère altier que, devenue princesse, elle gouverna la Toscane, dont Napoléon l’avait faite grande-duchesse. Elle essaya de se rendre populaire, mais sans y parvenir. Ses excentricités, le désordre de sa conduite privée, le faste insolent de sa cour, la dissolution dont elle était environnée, l’impiété qu’elle affichait, tout se réunissait pour éloigner d’elle le cœur de ses sujets. Quant au pauvre Bacciocchi, il traînait à la cour de sa femme une existence effacée et résignée, trop heureux lorsque de nouveaux scandales n’ajoutaient pas au ridicule de sa situation.

Telle est la femme dont David nous a laissé un si vigoureux et si éloquent portrait, demeuré à l’état d’ébauche on ne sait pour quelle raison. Tout le caractère de cette fantasque princesse y est déjà marqué en termes précis, avec une facture impressionnante et un art supérieur. Le coloris de ce tableau est un peu froid, comme l’était toujours le coloris du peintre, mais la tête est bien vivante et justifie la réputation, désormais consacrée, de David portraitiste.

Élisa Bonaparte figure dans la salle XVII consacrée à la peinture française.

Hauteur: 0.91.—Largeur: 0.73.—Figure grandeur nature.

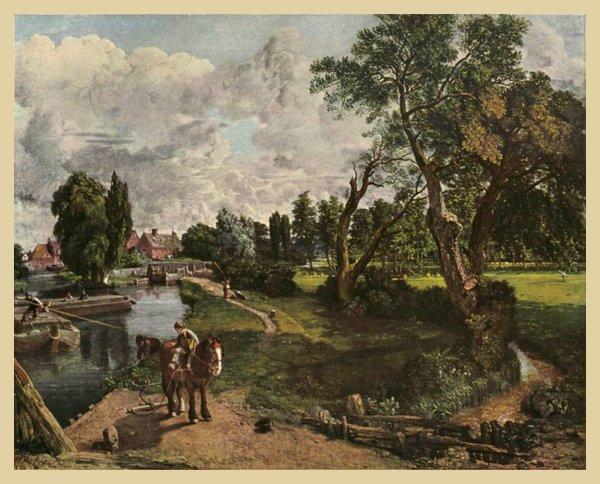

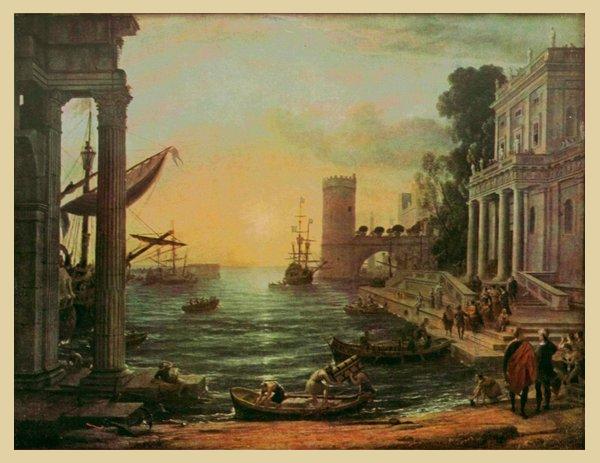

J. CONSTABLE

FLATFORD MILL

SALLE XX.—ÉCOLE ANGLAISE

71

Flatford Mill on the river Stour

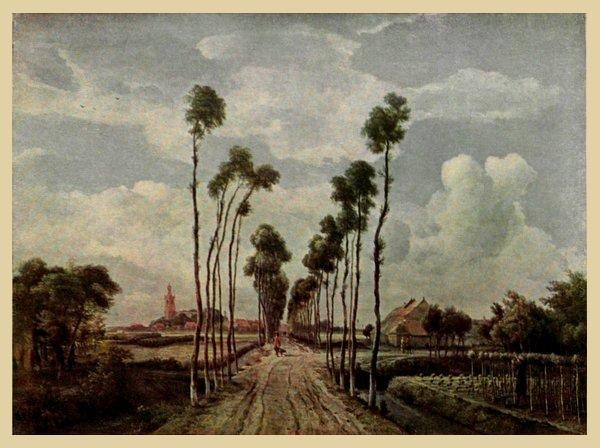

LE paysage représente un beau site de campagne, sur les bords

de la Stour, dans le riche comté de Suffolk. A droite, se

développent de vertes prairies éclairées par le soleil et

bordées par des rangées d’arbres. Le long de la rivière court le

sentier qui conduit au moulin de Flatford dont on aperçoit, dans le

fond, les bâtiments et les toitures rouges. Sur le cours d’eau se

meuvent des chalands qui viennent sans doute pour apporter le blé

à moudre ou remporter la farine. De minuscules personnages

s’occupent à la manœuvre ou vaquent à leurs occupations domestiques,

tandis que, sur le bord, un homme fixe une corde aux traits

d’un fort cheval chargé d’amener le chaland à la rive. A califourchon

sur le cheval et à demi retourné en arrière, un enfant suit d’un œil

intéressé les phases de l’opération. Tous ces personnages ne jouent

dans le tableau qu’un rôle épisodique, ils n’y tiennent pas plus

de place que dans les paysages de Claude Lorrain, mais ils

l’animent et l’égaient. Dans le ciel, de lourds nuages sont accumulés,

mais il reste encore assez de lumière pour éclairer la scène d’une

belle lueur, chaude et brillante.

Ce beau paysage compte parmi les meilleurs de Constable, le

plus grand paysagiste de l’Angleterre. La technique en est vigoureuse,

le dessin solide, la pâte nourrie, la couleur exacte et sobre. Les

plans successifs y sont supérieurement déterminés pour l’obtention

d’une irréprochable perspective et la lumière, ce protagoniste

72

essentiel mais difficilement saisissable de tout paysage, y joue son

rôle primordial: elle est partout dans ce tableau, largement épandue

sur la prairie ou discrètement insinuée dans les ombres des haies

qu’elle éclaire et réchauffe; elle s’accroche au faîte des branches, à

la cime des toits, à la tige des fleurs champêtres et colore de gaîté

l’atmosphère subtile qui court dans cette toile.La réputation de Constable comme paysagiste dépassa les frontières de son pays et sans doute aurons-nous l’occasion de signaler, dans de futures notices, l’influence considérable qu’il exerça sur notre école de 1830. Mais, en 1776, à l’époque où il vint au monde, les esprits et les âmes étaient, en Angleterre comme ailleurs, complètement fermés aux beautés de la nature. On ne la comprenait pas, on ne la supportait que comme accessoire dans un tableau, encore la fallait-il peignée, lustrée, élégante, pour servir de cadre à quelque bergerie ou d’écran à quelque personnage en habit d’apparat.

Né sur les bords de la Stour, Constable passa toute sa jeunesse en pleine campagne, à courir dans les champs, aux abords des moulins qui peuplaient la vallée. Comme il le dit plus tard lui-même: «Ce furent les scènes de mon enfance qui firent de moi un peintre.»

Dès son jeune âge, il sentit profondément la nature et désira la peindre. Il y fut encouragé par un ami qu’il s’était fait, un plombier-vitrier intelligent qui employait ses loisirs à brosser des paysages. Les parents du jeune homme songeaient à lui faire embrasser l’état ecclésiastique, mais ne se sentant aucun goût pour entrer dans les ordres, il préféra devenir apprenti meunier dans un de ces moulins qu’il aimait tant. Il n’y resta qu’un an, mais cette année passée en présence de la nature fit plus pour son talent que n’auraient pu lui apprendre tous les enseignements de l’Académie. Aux heures de loisir, il maniait le crayon et le pinceau avec une ardeur de néophyte. Sa famille ne voyait pas sans appréhensions le jeune Constable s’engager dans cette voie: «Mon fils, écrivait le père, 73 se destine à une bien misérable profession.» Lui-même eut des heures de doute. Quand il vint à Londres pour s’assurer «s’il avait des chances de réussir dans la peinture», il ne reçut aucun encouragement aux différentes portes où il frappa. Il était résigné déjà à abandonner son rêve quand il eut le bonheur, en 1799, d’être admis comme élève à l’Académie royale de peinture. A partir de ce jour, sa carrière est décidée, carrière toute de labeur et d’énergie, mais carrière presque obscure, que ne marque aucune distinction particulière. Paysagiste d’instinct, il se soumet volontairement à l’espèce de discrédit qui s’attache à son art. En 1802, il expose à l’Académie royale son premier tableau, sous le titre modeste: Paysage; il passe inaperçu. Il a alors 26 ans. A 43 ans, en 1819, il est élu membre adhérent de l’Académie royale et ne sera titularisé que dix ans plus tard. Son succès réel commence véritablement en 1824, avec son tableau célèbre: Hay Wain (La charrette de foin). Encore n’est-ce pas à Londres, mais à Paris que s’affirme sa réputation. Constable n’en est pas moins heureux d’hériter d’une petite fortune, car sa peinture ne suffit pas à le nourrir. Jusqu’à l’âge de 40 ans, il n’a pas réussi à vendre un seul de ses tableaux en dehors du cercle de ses amis. Et le phénomène tant de fois constaté se produit: ces paysages dont personne ne voulait à cette époque, on se les dispute aujourd’hui dans des enchères fabuleuses.

Le Flatford Mill (Moulin de Flatford) fut peint en 1817. Constable avait alors 41 ans. Dans cette admirable peinture se résument toutes les qualités de l’illustre paysagiste anglais, que Goncourt appelait le grand, le grandissime maître. Elle figure dans la salle XX, réservée à la peinture anglaise.

Hauteur: 1 m.—Largeur: 1.27.—Figures: 0.30.

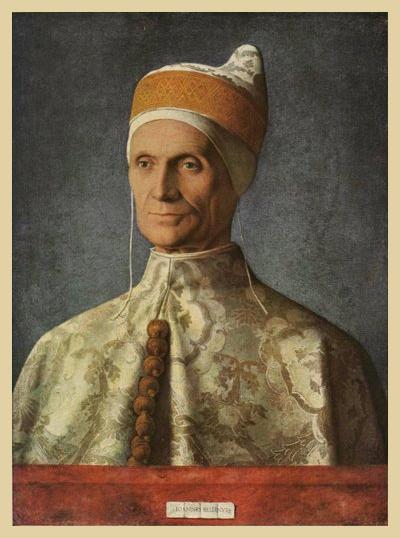

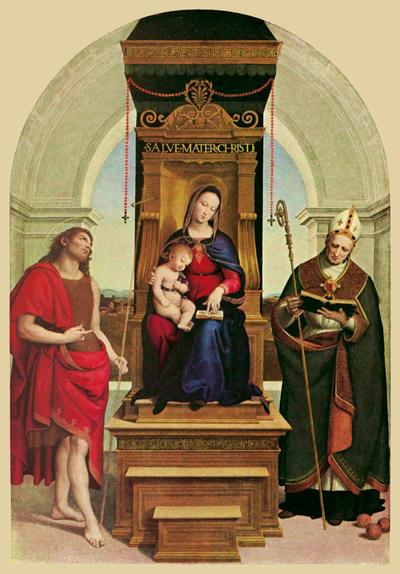

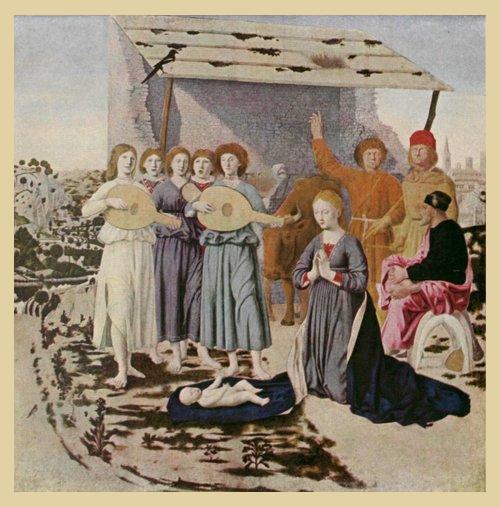

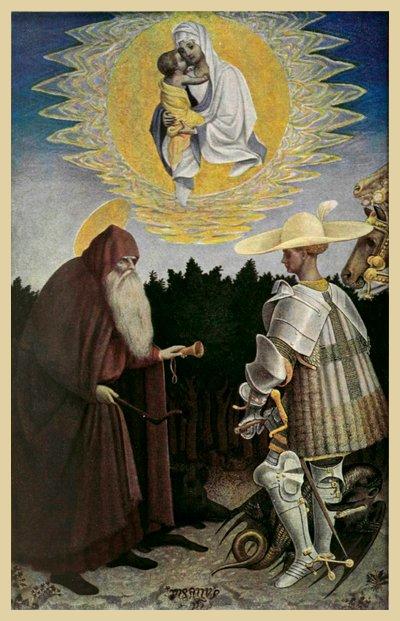

GIOVANNI BELLINI

LE DOGE LORÉDAN

SALLE VII.—ÉCOLE DE VENISE ET DE BRESCIA

77

Le Doge Lorédan

GIOVANNI BELLINI et son frère Gentile Bellini avaient

appris la peinture dans l’atelier de leur père, Jacopo Bellini,

artiste vénitien de grand talent. Celui-ci, loin de jalouser ses

fils, se montra tout heureux quand il vit leur mérite éclipser le sien

propre. Il les encourageait avec tendresse, car, disait-il, «il faut que

Gentile dépasse Jacopo et que Giovanni l’emporte encore sur Gentile.»

L’avenir justifia la prédiction du père. Des trois Bellini, Giovanni

fut le plus grand et le plus habile en son art. A une époque où son pays

regorgeait d’artistes de talent, il eut la gloire, partagée avec Mantegna,

de présider en quelque sorte à la première renaissance de la peinture

en Italie; il fut le plus délicat et le plus distingué des maîtres. Venu

au monde en un temps où s’élaborait en Europe un mouvement

général d’affranchissement intellectuel et moral, il forma la transition

entre la froide tradition des maîtres ascétiques et le glorieux

épanouissement des Véronèse et des Titien; il fut le maillon qui souda

l’un à l’autre les deux tronçons de cette chaîne. Il conserva quelque

chose de la naïve conception et de l’hiératisme de ses aînés, mais sa

souplesse, sa largeur de dessin, sa vigueur de coloris annoncent déjà

une ère nouvelle, où ses élèves entreront d’un pas victorieux.Mais si, par sa technique, Bellini prépare la voie aux grands Vénitiens de la Renaissance, il reste fidèle, dans le choix des sujets, à la tradition qui lui fut transmise par les siècles. Il est le dernier peintre véritablement religieux de l’école vénitienne. Plus tard il traitera, pour 78 le compte du Conseil des Dix, des sujets relatifs à la vie nationale; mais s’il consent à abandonner ses Vierges et ses Maternités pour célébrer les fastes de la cité, il se refusera toujours à verser, comme Mantegna, dans le paganisme envahissant. Il verra ses jeunes émules ou ses élèves, comme Giorgione et Titien, peindre des églogues court vêtues ou glorifier les dieux et déesses de l’Olympe, sans que lui vienne la pensée de se mettre au goût du jour. Sur le déclin de sa longue vie, il accepte, après bien des atermoiements, une commande d’Isabelle d’Este pour un sujet profane et accepte même un acompte de 25 ducats sur la somme de cent ducats convenue pour le travail. Mais, quand il s’agit de s’exécuter, le vieux peintre temporise, cherche des prétextes, tantôt feignant la maladie, tantôt objectant ses travaux au Palais Ducal, tantôt se confinant à la campagne. Vianello, le représentant d’Isabelle à Venise, se désole, la duchesse se fâche et déclare «ne pouvoir supporter plus longtemps les étranges procédés de Bellini». Elle charge son agent de déposer une plainte contre le peintre entre les mains du doge Lorédan. Celui-ci aime Bellini, peintre officiel de Venise; il intervient officieusement et Bellini, de guerre lasse, répond: «J’ai là une Nativité presque terminée; si la duchesse veut bien l’accepter, j’en serai très heureux.» Et il la lui expédie avec une lettre d’excuses. Ce n’était pas tout à fait ce qu’avait désiré Isabelle d’Este, mais devant la beauté du tableau, tout son ressentiment s’évanouit et elle écrivit au peintre: «Votre Nativité m’est aussi précieuse qu’aucune autre de mes peintures.»

La renommée de Bellini s’était étendue bien au delà des frontières de l’Italie. Albert Dürer, quand il vint à Venise, se plut à le fréquenter et nous trouvons, dans les écrits du grand maître allemand, le témoignage d’une estime qu’il ne prodiguait pas, surtout aux peintres de la péninsule. «Tout le monde me dit, écrit-il, combien il est honnête et j’ai tout de suite été porté vers lui. Il est très vieux (Bellini avait alors quatre-vingts ans), mais il est encore le meilleur pour la peinture.» 79 Il serait difficile pour un peintre de souhaiter une plus glorieuse consécration.

Telle était sa réputation que le sultan Mahomet II, le vainqueur de Constantinople, désira se faire peindre par lui et le demanda à la République de Venise. On ne sait pour quelle raison, son frère Gentile fut envoyé en Orient à sa place. Sans doute, la Seigneurie tenait à conserver près d’elle un artiste qui était le premier de son époque et, de plus, son peintre officiel. Cette qualité comportait, avec une très belle rétribution, d’importantes prérogatives, entre autres celle d’exécuter ou de diriger toutes les peintures dans les palais de la cité, et celle de peindre les Doges au pouvoir. C’est donc à titre de peintre officiel qu’il peignit le portrait du doge Lorédan, que nous donnons ici.

Le premier magistrat de Venise est représenté dans le bizarre et somptueux costume de sa fonction. Sur sa tête est posé un bonnet étroitement serré, qui cache les cheveux et les oreilles et se relève en pointe par derrière. Il est vêtu d’une magnifique robe en soie brochée où se révèle le goût des Vénitiens du XVe siècle pour les belles étoffes. Mais la merveille, dans ce tableau, c’est la tête énergique et sévère du doge; l’œil dur, les lèvres minces et les traits accusés disent assez le caractère ombrageux et cruel qui poussa Lorédan à instituer l’Inquisition d’État et le Conseil des Dix, dont la terrible tyrannie fit trembler Venise pendant deux siècles.

Dans ce portrait, le dessin, le coloris et l’expression du caractère sont également admirables.

Le Doge Lorédan est posé sur un chevalet dans la salle VII, réservée aux écoles de Venise et de Brescia.

Hauteur: 0.61.—Largeur: 0.44.—Figure grandeur nature.

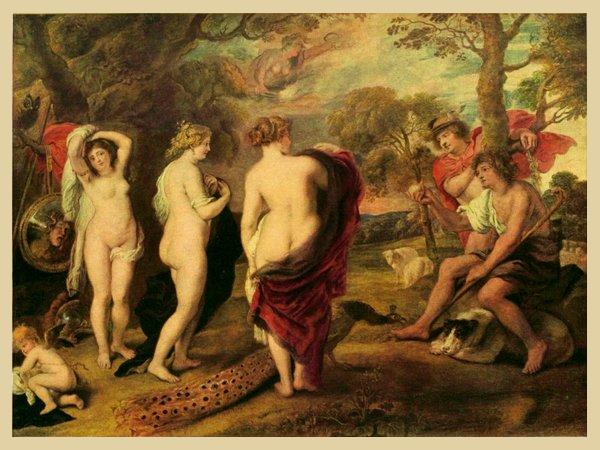

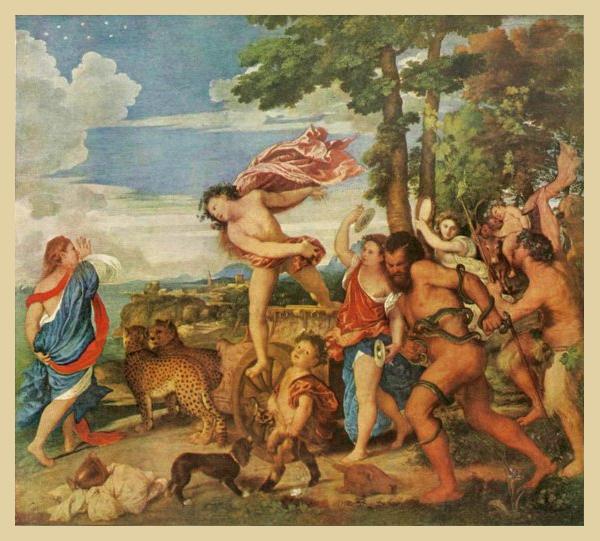

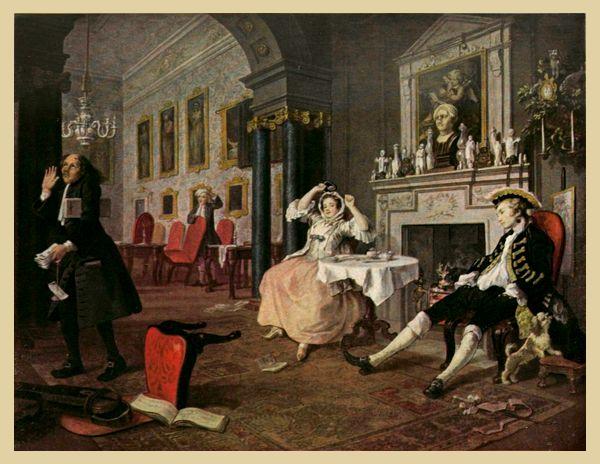

RUBENS

LE JUGEMENT DE PARIS

SALLE X.—ÉCOLE FLAMANDE

83

Le Jugement de Pâris

RUBENS a situé le célèbre épisode mythologique dans un

magnifique paysage agreste où les teintes dorées de l’automne

se marient à la rouge splendeur d’un ciel couchant. On serait

presque tenté d’oublier les acteurs principaux du drame devant la

prodigieuse habileté du peintre qui, en touches d’une vigueur

incomparable, recule sa perspective jusqu’aux plus lointaines

profondeurs de l’horizon. Quand Rubens s’avise d’aborder un genre,

quel qu’il soit, son œuvre se trouve immédiatement marquée de sa

griffe géniale; il se pousse du premier coup jusqu’aux plus hautes

cimes, il proclame en traits de feu son inégalable supériorité.

C’est dans ce prestigieux décor de nature que se déroulent les

phases de cette dispute célèbre dont les effets mirent le feu au

monde antique. On connaît la légende: Junon, Minerve et Vénus,

toutes les trois puissantes déesses de l’Olympe, prétendaient

également au sceptre de la beauté et cette éternelle rivalité, troublait

le séjour des dieux et divisait les immortels. Pour vider une querelle

que leurs pairs n’osaient pas juger, les trois déesses résolurent d’un

commun accord de s’en remettre au jugement d’un habitant de la

terre. L’arbitre choisi fut le jeune Pâris, second fils de Priam et

d’Hécube, le même qui, plus tard, ravit Hélène, femme de Ménélas.

C’est à cette scène du jugement que nous fait assister Rubens dans

son magnifique tableau.Assis sur une roche, au pied d’un arbre, Pâris tient à la main la 84 pomme qu’il décernera à la plus belle; il est lui-même bien digne de porter une telle sentence, car il possède la noblesse et la beauté d’un jeune dieu. Tout près de lui, debout, appuyé contre ce même arbre, Mercure, reconnaissable à son caducée, assiste à tous les détails de cette scène. Il paraît d’ailleurs plus amusé qu’anxieux. Par contre, aux pieds de Pâris, un énorme molosse est endormi, la tête allongée sur ses pattes, absolument indifférent à ce qui se passe autour de lui.

Et, devant leur juge, les trois déesses ont comparu, leur nudité splendide à peine voilée par les manteaux que soutiennent leurs mains. Voici Junon, reine des dieux, vue de dos, le bras droit replié soutenant un manteau de pourpre et tournant sa tête altière vers Pâris, en ayant l’air de revendiquer comme un droit de son rang le prix de la beauté. Sur ses pieds, le paon, son emblématique oiseau, étale sa large queue diaprée et soyeuse. Plus loin, Minerve, les bras relevés autour de sa tête brune, semble vouloir mettre en valeur tous ses avantages. A un arbre, derrière elle, sont accrochés ses attributs guerriers, le bouclier où figure une tête de Gorgone; le casque est posé à terre. Entre Minerve et Junon, se tient Vénus, fille de l’onde, en une pose pleine de modestie, les deux bras croisés sur la poitrine et regardant Pâris qui lui présente la pomme, signe de son triomphe. Tandis que l’attitude de Junon trahit la colère, et celle de Minerve le dépit, on lit sur le visage de la blonde déesse la surprise agréable de sa victoire sur ses deux rivales.

Ce jugement proclame Vénus déesse de la beauté, mais il ne termine pas le différend, il ne fait que l’envenimer. Sans s’en douter, Pâris amasse contre lui et sa race la rancune de deux puissantes divinités et son verdict coûtera à la famille de Priam la perte de Troie. Dès maintenant, nous avons comme un présage de tous les maux qui se préparent: dans le ciel apparaît une sorte de furie échevelée brandissant la torche de l’implacable discorde.

85 Tout est admirable dans ce tableau. Nous avons dit la beauté du paysage, il nous reste à signaler l’harmonieux équilibre de la composition où tout est disposé supérieurement pour répartir l’intérêt. Rubens s’est joué comme à l’habitude de la difficulté; il y a déployé une merveilleuse fécondité d’invention et l’ensemble de l’œuvre est éclatant, superbe, fastueux.

Ce qu’il convient de noter, c’est la conception toute particulière qu’a Rubens de la beauté féminine. Regardez les trois déesses: le peintre a traduit à la flamande la beauté grecque des Olympiens. Ces nobles formes étaient trop pures et trop tranquilles pour son pinceau turbulent; il les a mouvementées, arrondies, soufflées, bossuées de muscles, mais par la couleur il leur a conservé la divinité. C’est bien la chair des dieux, pétrie d’ambroisie et de nectar; rose comme la pourpre royale, blanche comme la neige de l’Olympe. Le torse de la Vénus semble fait avec des micas de Paros et des étincelles d’écume. Jamais la peinture n’a été plus loin pour le rendu de la chair, le grain de l’épiderme et le frisson mouillé de la lumière.

Le Jugement de Pâris figure dans la salle X, consacrée à la peinture flamande et hollandaise.

Hauteur: 1.44.—Largeur: 1.90.—Figures: 0.65.

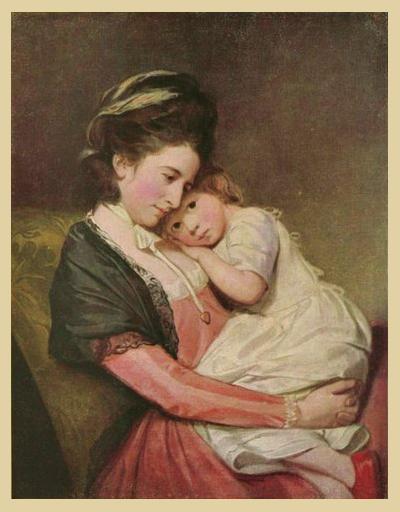

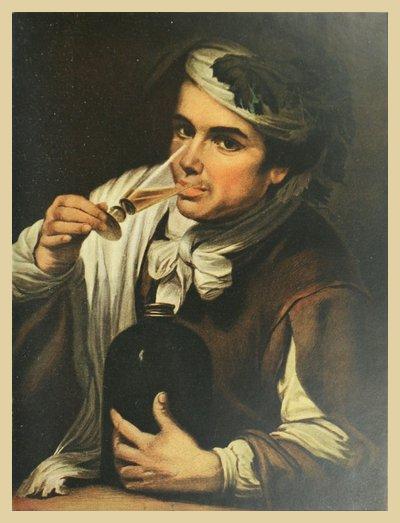

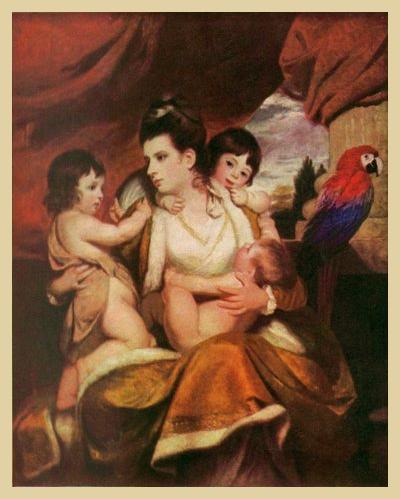

ROMNEY

UNE DAME ET SON ENFANT

SALLE XIX.—VIEILLE ÉCOLE ANGLAISE

89

Une dame et son enfant

ON pourrait appeler Romney le Nattier de la peinture anglaise.

Comme le maître français, il fut le portraitiste préféré des

femmes, parce que, comme lui, il sut les parer de tous les

charmes, même quand la nature s’était montrée le moins indulgente

pour elles. Nul pinceau ne fut plus conciliant, plus flatteur, plus habile,

car il joignait à son art d’embellir celui, plus difficilement réalisable,

de faire ressemblant. Sous des apparences manifestement avantagées,

ses modèles les plus disgraciés se reconnaissaient et, qui plus est, on

les reconnaissait.

Aussi, la vogue dont jouissait Romney à Londres s’égalait à celle

de Reynolds et de Gainsborough. Toute la «gentry» anglaise se

pressait à son atelier de Cavendish Square. Il était parvenu presque

sans effort, par un heureux concours de circonstances, à ce degré de

réputation. Sa bonne étoile avait guidé sur la voie glorieuse l’apprenti

menuisier de Beckside. Lorsqu’il parut à Londres, venant de sa

province, il n’avait que le goût du dessin, avec peu de science. Son

maître, un certain Steele, n’avait qu’une valeur médiocre et le jeune

artiste en tira tout ce qu’il put, c’est-à-dire bien peu de chose. Mais il

comprit combien il serait hasardeux de tenter la fortune avec un aussi

mince bagage technique, et sa résolution fut vite prise: il alla apprendre

son métier en Italie, au contact des maîtres. Rien ne le retint en

Angleterre, pas même sa famille. Avec une belle désinvolture, qui fait

plus honneur à son esprit de décision qu’à ses qualités de cœur, il

90

abandonna sa femme et ses enfants. Il ne revint pas auprès d’eux

à son premier retour d’Italie, mais il continua à mener une

existence vagabonde et décousue, courant de ville en ville, et vivant de

portraits qu’il exécutait au rabais et que son énorme facilité lui

permettait de brosser en quelques heures. Son voyage en Italie l’avait

enthousiasmé; il y revint et, cette fois, il semble qu’il en ait retiré

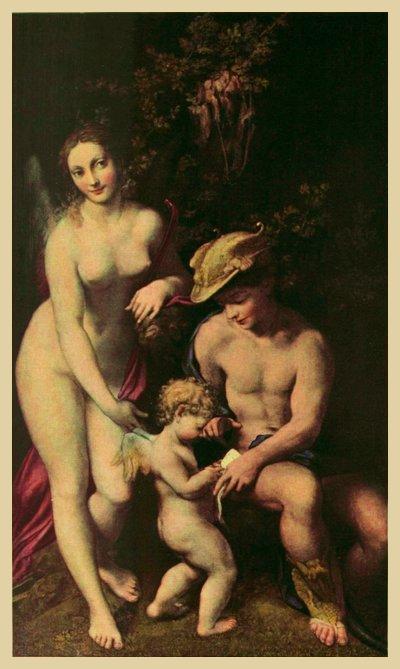

plus de fruits. Il s’adonna surtout à l’étude de Raphaël et du Corrège,

ses idoles, et lorsqu’il revint, il se trouva complètement armé pour lutter