7 Delicious Recipes from

Emily Dickinson

It’s fairly common knowledge these days that everyone’s first favorite poet Emily Dickinson was also no slouch in the kitchen. In fact, as others have pointed out, in her lifetime she was almost certainly more famous for being a baker than she was for being a poet. Her creative and culinary works even seem to have influenced one another—or at least she worked on a number of poems in the kitchen, while she worked. So it’s no surprise that the Dickinson family recipes—a few of which have survived—fascinate the faithful. At least, I know that personally I decide to make one of them every year (only to become daunted or otherwise forget). So in case you’d like to impress everyone you know by arriving at your next seasonal gathering with a picnic basket full of Emily Dickinson-approved recipes (and especially if you have a boat full of eggs you need to unload), here are a few recipes to choose from. Perhaps they will even inspire some verse from your friends and neighbors.

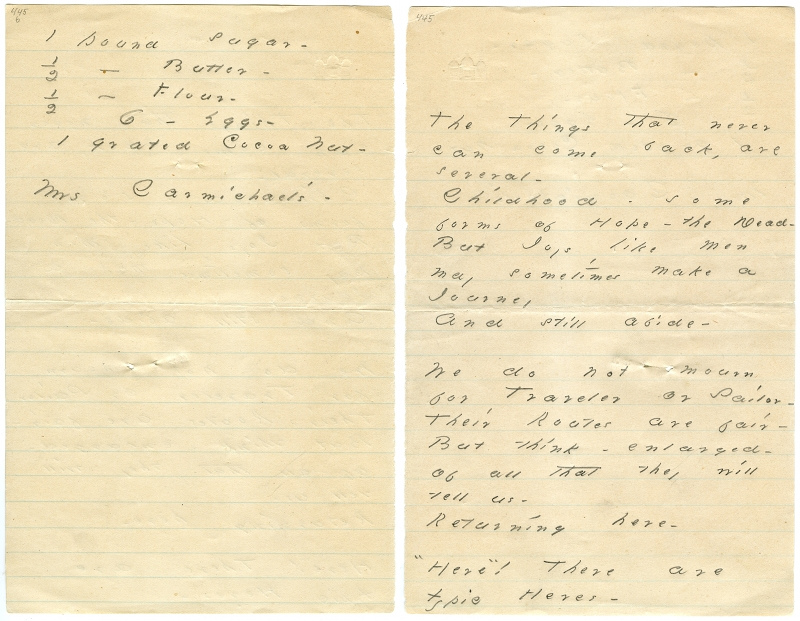

Coconut Cake:

According to the Emily Dickinson Museum website, Dickinson wrote many poems in the kitchen—often on the backs of labels, recipes and other papers, and these reveal that the kitchen “was a space of creative ferment for her, and that the writing of poetry mixed in her life with the making of delicate treats.” After all, what better way to fill the long interval between putting something good in the oven and getting to eat it? Indeed, on the back of this recipe for coconut cake, apparently passed on to her by a Mrs. Carmichael, Dickinson drafted a poem:

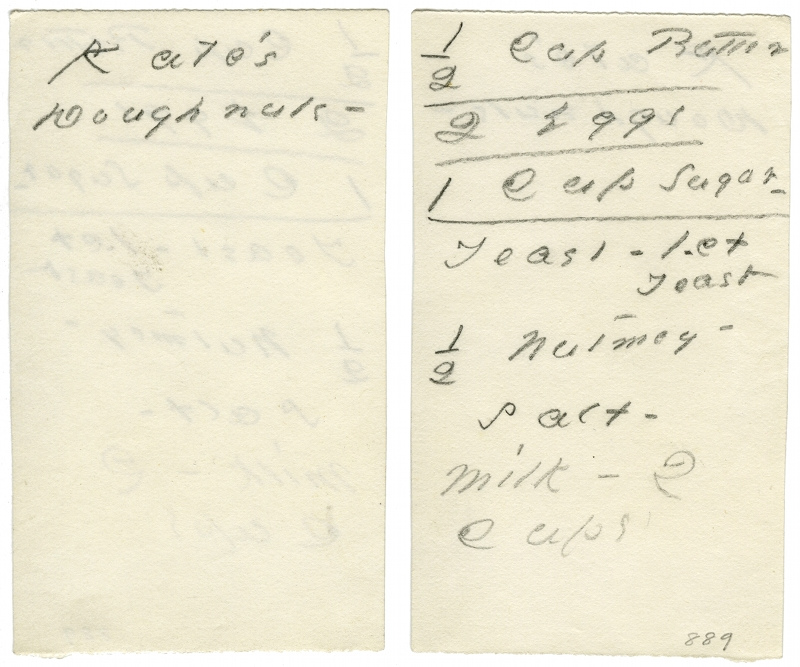

Doughnuts:

On the back of this recipe, Dickinson has written simply “Kate’s doughnuts”—the identity of Kate is a mystery. Perhaps these doughnuts were their own poems.

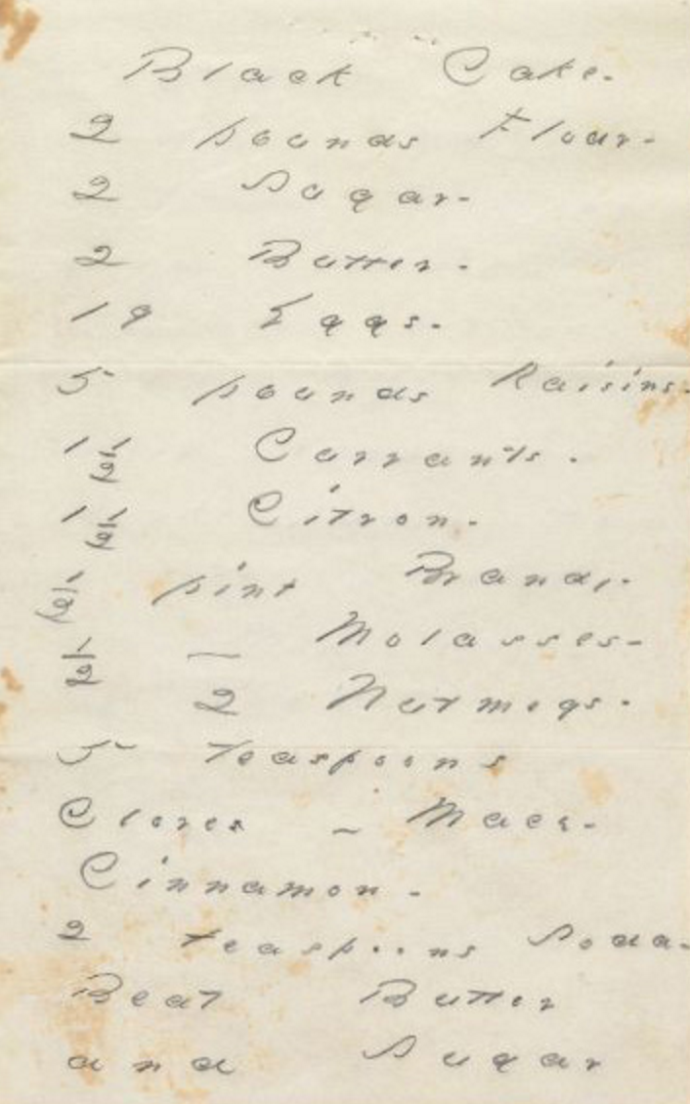

Black Cake:

The Library of America blog notes that the Dickinson family had several “lawless cake” recipes, and that Emily’s father “would eat no bread except that baked by her.” All I have to say is that 19 eggs is lawless indeed. So is the fact that, once baked, but before the brandy was poured in, this cake weighed almost 20 pounds. NB: The Washington Post published an updated version of the recipe in 1995, apparently more suited for “20th-century palates.” That one only calls for 13 eggs.

Gingerbread:

The editors of Emily Dickinson: Profile of the Poet as Cook add these instructions: “Cream the butter and mix with lightly whipped cream. Sift dry ingredients together and combine with the other ingredients. The dough is stiff and needs to be pressed into whatever pan you choose. A round or small square pan is suitable. Bake at 350 degrees for 20–25 minutes.” There is no attendant recipe for the glaze, although Dickinson did apparently glaze her gingerbread, and sometimes garnished it with an edible flower or two.

According to Emily Dickinson museum tour guide Burleigh Mutén, whenever Dickinson saw children playing in her family gardens, “she headed for the pantry, filled a basket with cookies or slices of cake—often gingerbread—carried it upstairs to a window in the rear of the house (so their mothers wouldn’t see), and attached the basket to a rope to slowly lower it to the “storm-tossed, starving pirates” or the “lost, roaming circus performers” eagerly waiting below.” When she was out of baked goods, she would send down two cups of raisins, which the children ate like candy.

Corn-Cakes:

and

Rice-Cakes:

These two recipes were originally published by Dickinson’s cousin, Helen Bullard Wyman, in a summer 1906 issue of The Boston Cooking-School Magazine. “Rice-cake was considered our very best ‘company cake’ in my childhood,” she wrote, “being carefully placed in a large tin pail, and only used when outside persons came to tea. The rule was much richer than this, however, and it was baked in sheets, very thin, and cut into squares after coming from the oven. Mace (or nutmeg) was the spice always used in it.”

Lyman’s Rye and Indian Bread

Add salt and molasses to corn meal. Pour boiling milk over it. Add cold buttermilk to the rye flour, plus baking soda. Mix entire ingredients together, adding the stewed potato. No rising time is needed. When firm, place in a round bread pan; bake at 440 degrees for 2 1/2 hours. When done, cover loaf with butter and a towel to help retain moisture.

Makes 1 loaf.

I found this one on a forum called CivilWarTalk, so my thanks to Donna from Kentucky. Lyman refers to Joseph Lyman, one of Dickinson’s cousins. Perhaps this is the very recipe with which Dickinson won second prize at the 1856 Amherst Cattle Show?